by Jack Cashill

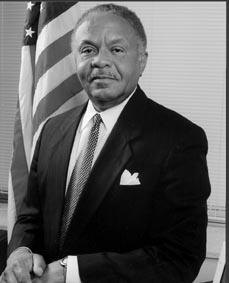

Former Kansas City, Missouri School Superintendant, Dr. Benjamin Demps

"Inside? Leroy, c'mon!"

Fortunately, his wife Anna was on my side of the debate, and we all but dragged him to the outdoor part of the restaurant, the Classic Cup on the Plaza, not exactly Leroy's choice in the first place. I ordered a shrimp and artichoke salad. Leroy had lived too long for that sort of stuff. He passed.

Kansas City was abuzz that day as it had not been in a long time. Benjamin Demps had quit as Superintendent of the Kansas City School District the day before, and everyone was talking about it. With the growth of the suburbs and the editorial red-lining of The Kansas City Star, a medium that fewer and fewer people read these days, it is a rare day when any issue galvanizes the whole metropolis. But this was one such day.

The Hyrnes know the District perhaps better than anyone in Kansas City. After Anna's failed run for the School District, she and Leroy wrote and published The Greed Within Them, a breathtakingly honest book and probably the best one ever written anywhere on inner city politics. Yet for all for their honesty-perhaps because of it-the establishment media ignore the Hyrnes. Inside the restaurant, for instance, Barbara Shelley of The Star was interviewing school board member, Al Mauro.

Although we had scheduled this lunch before the Demps thing broke, I had to get the Hyrnes' take on it. Unlike the rest of Kansas City, neither Anna nor Leroy was particularly jazzed by the Demps' imbroglio. The Hyrnes had seen it all before. "Ah, they're just up to the same old stuff."

I asked Anna who the "they" was. As she and Leroy described it, the "they" is a shifting, amorphous coalition of largely self-seeking politicos and hangers-on, mostly but not exclusively black, who want to control the perks and the patronage of running the school district.

Although there is no permanence to this coalition, Anna identified activist Clinton Adams, the Reverend Fuzzy Thompson, Freedom, Inc. and certain union people as participants. On the school board, this coalition is represented by the five board members who had voted to oust Demps a week or so before he quit. Polite Kansas City has known about the "they" for years but has chosen not to talk about them. But this time, it was all pretty close to the surface.

Speaking of the racial divide on the school board issue, former mayor Emmanuel Cleaver was quoted by The Star as saying, "I don't think there's any question that the situation is critical. It may be the worst it has been ... ever." Cleaver, who has learned to finesse the boundaries between the "they" and the "us," was quietly angling for the top job.

At a hearing on Friday, April 27, U.S. District Judge Dean Whipple, as reported in The Star, publicly acknowledged the "they" as well, saying he was "concerned about an individual or individuals, whom he would not name, ordering employees around or dictating what they should or should not do." Whipple went so far as to tell interim School Superintendent Bernard Taylor that he "not let that individual walk the halls of the administrative building." The Star openly suggested that the individual was attorney Clinton Adams.

Following the lead of the courts and the media, public sentiment has been roused against the largely nameless "they" to a near universal scorn. After running a series of anti-"they" letters, a frustrated Elizabeth Alex on 41 News commented that 41 would be pleased to run "pro" letters. It's just that they had not received any. The papers haven't gotten many either. The following from The Star almost perfectly captures the prevailing public mood:

"I applaud Superintendent Demps for his courage and speaking out for the best interests of the children of the Kansas City School District. If the current school board knew what they were doing, the district wouldn't be in the state that it is in now. . . I hope that someone will listen to reason in the Missouri legislature and take action." In fact, it was Demps' own personal appeal to the State of Missouri to take over the School District that aroused the ire of a majority of Board members. "I want the state of Missouri to get the political courage to do something for a district that for 20-something years has thousands of kids who have not been educated," Demps told Missouri lawmakers in February. "That's what I want. That's what. I want. That's what I want." From that moment on, despite wide public support, Demps was toast.

HOW THE "THEY" WORKS

As we were leaving the Classic Cup that day, I stopped and talked to Al Mauro. A retired Kansas City Southern exec, Mauro is one of the last of the genuinely "good citizens" in Kansas City proper. No greater burden can a good citizen here bear than to run for the school board, a thankless, unpaid and ultimately disillusioning task. Mauro was one of the four on the board to support Demps.

I had not previously met his lunchmate, Star columnist Barbara Shelley. In a flippant aside, I suggested to her that The Star itself was not fully above the fray in this issue and left it teasingly at that.

I was referring to a minor but telling incident from ten years prior that taught me how the "they" work. To cut to the chase, the school board's marketing committee had voted 8-1 to award me a $175,000 marketing contract. This took some guts. I had just written a rather damning column on the magnet plan for Ingram's Magazine and had refused to share a wasteful half of the contract with a particular minority graphics firm as I was asked to do.

Then all hell broke loose. The Star launched a series of articles and a piece by then columnist Art Brisbane condemning me as an opportunist. To its credit, the Board hung with me.

And then Clinton Adams called. Adams obviously did not like to see a patronage opportunity of this size squandered. He told me that if I did not back out of the contract, I could expect to see a column in The Star denouncing me as a racist. I didn't back down.

Neither did The Star. No more than two days later, Star columnist Rhonda Chriss Lokeman compared my Ingram's article to Jesse Jackson's "insensitive and idiotic description of New York as Hymietown." The opportunism charge I could understand, but this one came out of nowhere. My article was an attack on stereotypes, and everyone else knew it. Regardless, as Lokeman explained to me, "When you expose stereotypes, you perpetuate them." The flames of racial McCarthyism nicely fanned, the board started to waver, and I quit the contract before my show trial could begin on Channel 2.

As I learned the hard way, democracy only works when the media are vigilant. When they are complicit, we are all in trouble.

WHITHER DEMOCRACY?

At lunch, I discussed Adams with the Hyrnes. We all agreed that he had mellowed some over the years. When I first met the hulking Adams ten or twelve years ago, he was a flat-out bully. Teachers and administrators feared him. I had seen him in action. Their fears did not seem unjustified.

For all that, Adams cared and still does care deeply about the District. As testament, his daughter just graduated from Lincoln Prep. I talked to him at length a few months back about The District. Always smart, Adams had begun to temper his intelligence with discretion. He has a keener sense of District problems than just about anyone I have talked to.

Adams also remains one of the few champions of local democracy left in the District. After 23 years of federal control, polite Kansas City has all but lost the habit. A little background on how this happened. In 1977, when Jimmy Carter plucked Russell Clark from obscurity to serve as a Federal District judge, the courts had shifted from prohibiting racial discrimination to insisting upon it. Indeed, by 1977, the momentum of the courts was so strong, and its direction so defined, that few in either party cared-or dared-to get in its way.

Even Clark's critics acknowledge that Jenkins v. Missouri was a sympathetic case. When he assumed it, black students had become the majority in the District, but the voting majority remained white. For a mix of reasons, voters rejected one initiative after another to fix up the schools. Buildings were crumbling, test scores were dropping, and white kids were leaving.

Lacking proof to hold the suburban districts liable, Judge Clark chose an alternate plan: he would desegregate the KCMSD by attracting white students from the suburbs. To build the schools, the state and the District would have to foot what would prove to be a $2 billion dollar bill.

Kansas City citizens were clearly not up to the task. No fan of democracy, Judge Russell Clark unilaterally doubled taxes on Kansas City property owners in 1985 and raised the payroll taxes on its work force. He also levied a huge assessment against the state of Missouri and launched the biggest one man building project since Ramses II, including the construction of 17 new schools and the rehabilitation of 55 old ones.

But after twelve years and billions of dollars, Clark had come to doubt whether he could ever solve the District's problems. Too many fatherless children, he came to see. Too little motivation at home. "I don't know," he mused, "if the disparity (between black and white students) can ever be eliminated. Probably not."

TOO MANY CHEFS

And so Judge Clark handed the case over to Dean Whipple. At this time, Whipple was already running the Kansas City Housing Authority, Jackson County jails, and Jackson County foster care. Indeed, no community beyond the beltway had labored under such an oppressive Federal hand since reconstruction. And no American had exercised such unlimited suzerainty over so many people since McArthur in Japan.

But the Judiciary could persist because the local establishment put up so lame a fight. Our leading citizens had abandoned self-rule as docilely as the Vichy French. If there was any protest, it was directed then, like now, against the one institution that struggled to maintain a vestige of democracy, the Kansas City School Board.

For all his power, Whipple quickly wearied of it and relinquished control two years ago. "Too many chefs in the kitchen," he summed it up astutely. No matter. An appeals court handed it back.

After 23 years of powerlessness, Kansas City had lost confidence in its ability to manage its own schools. When the Feds briefly stepped out, the momentum grew to turn the School District over to the state. For all the fine work the good citizens on the School Board do, it is they who have led the charge to abandon local control.

School board member Patricia Kurtz, for instance, applauded Demps' appeal to the State. With the state unlikely to step in, Kurtz believes that "the only assistance I can come, perhaps, by increasing the oversight role of the Desegregation Monitor, Dr. Charles McClain."

And yet as Whipple noted when he tried to give up the case, "Despite the expenditure of vast sums . . . and the passage of 40 years since the end of official, de jure, segregation, the district still struggles to provide an adequate education to its pupils."

He understates the failure. After 23 years of federal control, billions of dollars in expenditures, and a six to one employee to student ration, only one of the 80 or so schools in the Kansas City District does not qualify as a "concerned school" by Missouri state standards.

A school qualifies for "concerned" status if more than 15% of its students fall into the lowest two categories on the Missouri Assessment Program tests. At Lincoln Prep, in the math test, 34% of the students were in the lowest two. Lincoln Prep was the best of the high schools. Van Horn, which did second best, had 89% of its students in the lowest two categories. At seven city high schools, the number was 97% or higher.

REMEMBER KOSOVO

According to wire reports, the Kosovar crisis started in 1989 when Belgrade "stripped Kosovo of its autonomy and imposed its education curriculum." Secretary of State Madeline Albright would not let this stand. Recognizing "the importance of the Kosovars' having their own education laws," she insisted at Rambouillet on this one key provision--that "an elected Kosovo legislature will run education, justice and other functions in a de facto form of autonomy." In other words, the Kosovars would get to elect their own dang school board and operate without meddling from a Belgrade judge. We went to war to assure this.

Maybe it is time to do the same in Kansas City. Maybe it is time to give democracy a chance and check its natural excesses not through the courts or through the states-but through a vigilant local media and an alert public. Indeed, were Anna and Leroy Hyrne to run the major daily newspaper, and not just their weekly radio show, I assure you all local politicians would toe the line.

Given the resources employed the last 23 years, Clinton Adams and the rest of the "they" could only have done better than the Feds. Indeed, if "they" gained real control, "they" might just try something the Feds and the state would never dare to do-deconstruct and start all over. After all, it's "their" children.