|

Frank Payne Sebree was just a kid in the

1860s, so it surely made an impression on him when Quantrill’s Raiders

plundered his family’s farm in Howard County, Mo. Frank James, not

yet a legend but soon to be, was among those that robbed the Sebree farm

of chickens and eggs and supplies on that day early in the Civil War.

Sebree grew up, became a lawyer, and moved to Marshall, Mo., just one

county over from Howard. He had established his reputation, had even served

in the legislature, when Governor Crittenden appointed him as special

prosecutor for a special case. On the second day of July, 1883, in Gallatin,

Mo., Sebree took up the interests of the people in the matter of a Winston

train robbery and murder. The defendant was Frank James.

The story would be even better if Sebree had won a conviction that July,

but in three separate trials for robbery and murder, the law could never

lay its claim on James. Still, Sebree did all right for himself—six

years later he came to Kansas City and started a two-man practice that

over the next hundred years would become the international, 528-member

firm of Shook, Hardy & Bacon.

A walk through the past of some of Kansas City’s top law firms is

like a walk through history. From the Civil War to the current conflict,

the attorneys in our town have been a part of the benchmark litigation,

policy and politics that have shaped our lives.

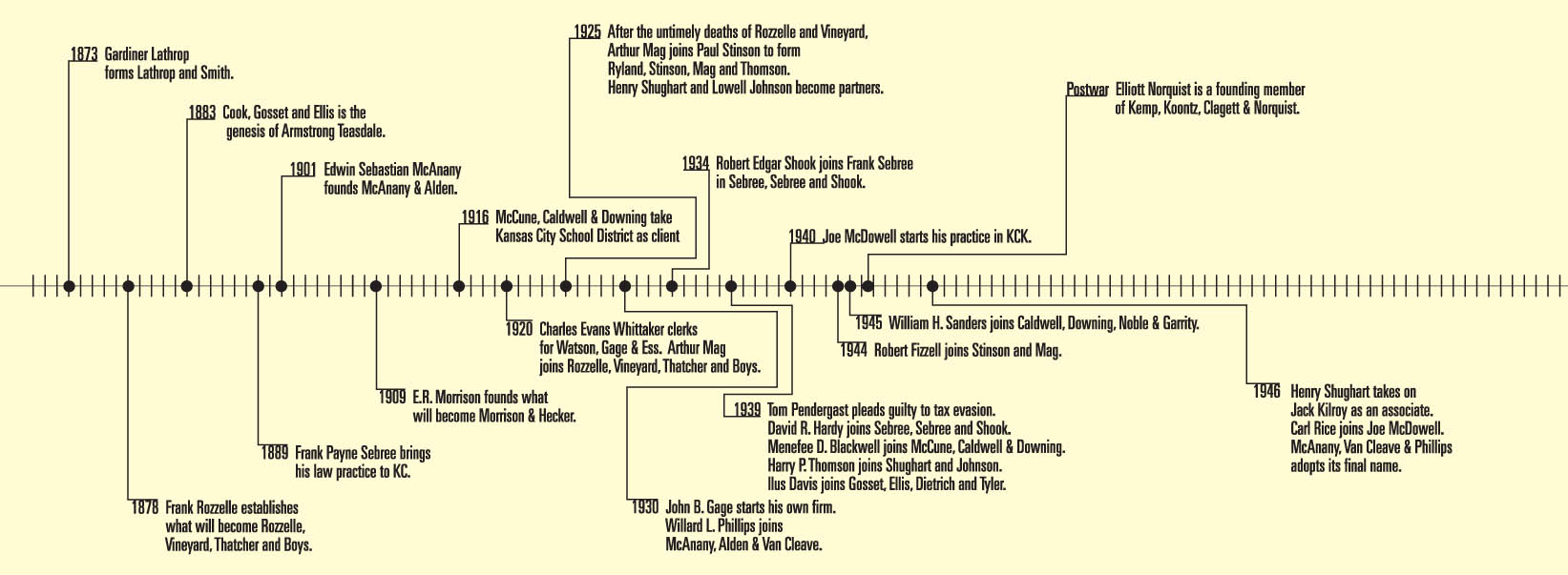

Frank Sebree became one of the pioneers in that history when he started

his Kansas City practice in 1889. But before him there was Gardiner Lathrop

in 1873, founding father of Lathrop & Gage, and Frank Rozzelle in

1878, founding father of Stinson, Mag & Fizzell. Whether or not their

names remain on the letterhead of their firms today, they have made a

mark on our city that will never be erased.

According to partner John Dods, self-proclaimed unofficial historian of

Shook, Hardy & Bacon, Sebree served as chairman of the park board

during the development of Kansas City’s boulevard system and the

Liberty Memorial, both landmarks that continue to set our city apart from

others. Rozzelle served as a city counselor, as a police commissioner

and as personal attorney to William Rockhill Nelson. He created a trust

for Nelson for the purpose of buying art for a museum, and he in fact

bequeathed his own estate to help build that museum. Rozzelle Court at

the Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art is named in his honor.

Lathrop & Gage still represents Gardiner Lathrop’s first client—the

Burlington Northern Santa Fe Railroad (known then as the Atchison, Topeka

& Santa Fe). Other long-term relationships were developed around the

turn of the century as well. One of the first clients of McCune, Caldwell

& Downing—formed in 1916—was the Kansas City School District

(KCSD). The district remains a client of the firm, although it’s

the firm rather than the client that has changed names. Today, legal counsel

for the KCSD is Blackwell Sanders Peper Martin, descendent of McCune.

One of the names that has survived through time is that of Henry Shughart,

who along with Lowell Johnson joined the firm of Rosenberger and Reed

in the early 1920s. There is some question whether Reed was already dead

or whether the name was a cover meant to deflect anti-Semitism from Rosenberger.

Either way, Rosenberger died in 1926, and the two associates found themselves

partners in the firm of Shughart and Johnson.

Arthur Mag found himself in a similar situation at about the same time.

He joined the firm of Rozzelle, Vineyard, Thatcher and Boys in 1920, and

was still an associate in 1924 when both Rozzelle and Vineyard died. One

of the remaining partners retired shortly after and the other became terminally

ill. Despite his youth and relative inexperience, Mag convinced Stern

Brothers, Schutte Lumber and Wright Liquid Smoke Company to remain with

him. He soon joined forces with Paul Stinson and I.P. Ryland to form Ryland,

Stinson, Mag and Thomson in 1925.

Over the next 15 years, John B. Gage and Joe McDowell started their own

firms while Robert Edgar Shook joined Sebree in the firm that would become

Sebree, Sebree and Shook. Gage and McDowell would go on to become mayors

of Kansas City, Mo., and Kansas City, Kan., respectively. A bumper crop

of bright associates came on the scene in the late ‘30s with David

R. Hardy joining Sebree, Sebree and Shook; Menefee D. Blackwell and John

Oliver joining McCune, Caldwell and Downing; Harry P. Thomson joining

Shughart and Johnson; and Ilus Davis joining Gossett, Ellis, Dietrich

and Tyler.

Kansas City in the 1930s, of course, belonged to Tom Pendergast. Among

his many activities during the Depression, he was an expert at winning

contracts for federal relief projects; his Ready Mixed Concrete company

built nearly every Kansas City building made of poured concrete at that

time, including Municipal Auditorium and City Hall. His political machine

reached a peak in the 1936 election when his candidates received 60,000

votes cast by ghosts.

Many of Kansas City’s law firms claim to have a forefather who was

instrumental in bringing down the Pendergast machine, but so many attorneys

have served in public roles over the city’s history, at least some

of those claims must be true. Ed Shook, as chairman of the board of election

commissioners at that time, helped put a stop to voting irregularities.

Before and after Pendergast pled guilty to tax evasion on May 22, 1939,

John Gage, William Kemp and Paul Koontz—all ancestors of Lathrop

& Gage—worked for the cleanup of local government. John Gage

was elected as the “Reform Mayor” in 1940.

Then there was the war. Not the war to end all wars, but the one after

that. Partners put law-firm expansion on hold while associates and law-school

grads went off to fight in World War II. It was only toward the end of

the war that things began to get back to normal. In 1944 Robert Fizzell

joined Stinson and Mag in their firm. In 1945, William H. Sanders joined

Blackwell at Caldwell, Downing, Noble & Garrity. In 1946, Jack Kilroy

was invited to practice with Thomson in the Law Offices of Henry M. Shughart.

Elliott Norquist became a founding member of Kemp, Koontz, Clagett &

Norquist.

Still, by today’s standards, firms were small. According to Ed Matheny

in his history of Blackwell Sanders called A Long and Constant Courtship,

the firm—then known as Caldwell Downing—“had six lawyers

in 1945, Shughart Thomson had four, Shook Hardy had four, and Stinson

Mag was regarded as a ‘factory’ with 12.” Matheny became

Caldwell’s 10th attorney in July of 1949, following his graduation

from Harvard Law School. The firm had leased space for only 10 lawyers,

believing that to be the optimum number to serve its clients.

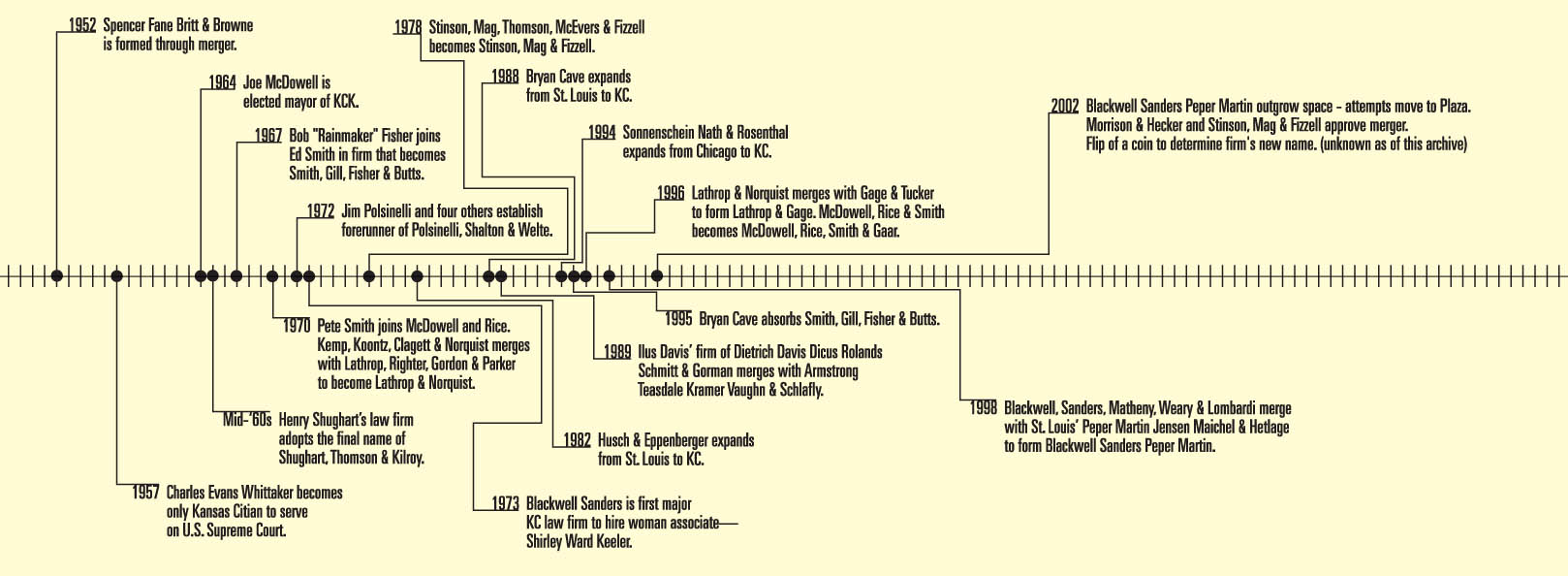

But, Matheny says, the firm’s litigation practice exploded during

the prosperous 1950s, and many other law firms saw their clientele grow

as well. Spencer Fane Britt & Browne was formed through merger, and

Ed Smith founded what would become Smith Gill Fisher & Butts. Blackwell

Sanders saw its work with the Kansas City School District heat up with

the case of Brown vs. Board of Education. And in 1958, David Hardy of

Shook, Hardy & Bacon won $200,000 for a policeman injured by a concrete

truck in the case of Moore v. Ready Mixed Concrete—the largest award

for a plaintiff ever in the state of Missouri. It was a double sweet justice

for a Shook lawyer to prevail against Pendergast’s old enterprise.

Hardy became the driving force behind Shook’s growth, according to

historian John Dods, with a case that came his way in 1962. John Oliver

of Blackwell Sanders had been representing the defendant in Ross v. Philip

Morris, a suit brought by a smoker with throat cancer in the U.S. District

Court in Kansas City. When Oliver was appointed to the bench in ‘62,

he had to relinquish the case. Because of the Moore verdict, David Hardy

looked like the next best option. All Philip Morris needed was a Missouri

lawyer to appear in a Missouri court just for this one case.

After two years of preparation, Hardy exonerated his client in a three-and-a-half

week trial, and Philip Morris knew it had found a new law firm. That single

case catapulted Shook, Hardy & Bacon to the forefront of product liability

defense.

The changing social environment of the early ‘60s began to impact

the legal profession. Ilus Davis, known for his deft handling of race

relations, became mayor of Kansas City in 1963. According to Promise and

Legacy—McAnany, Van Cleave & Phillips’ centennial history—that

same year the Wyandotte County Bar Association, in its conditions of membership,

agreed to strike the word “white” before “male.” It

would be three years later before the word “male” was stricken

from the constitution altogether.

Blackwell Sanders found itself on the cutting edge of social policy in

the 1970s in several ways. In 1973, it became the first major law firm

in the city to hire a woman associate—Shirley Ward Keeler—and

with her promotion in 1978, it became the first to include a woman partner.

Secondly, it and the Kansas City, Mo., School District became deeply embroiled

in the court-ordered desegregation of the district. McAnany, Van Cleave

& Phillips advised the Kansas City, Kan., School District in segregation

matters on the other side of the state line.

The 1970s, ‘80s and ‘90s became a time of both expansion and

merger for local law firms. Kemp, Koontz, Claggett & Norquist, for

example, merged in 1970 with Lathrop, Righter, Gordon & Parker to

form what eventually would become Lathrop & Norquist. Husch &

Eppenberger and Bryan Cave expanded into the Kansas City market from St.

Louis and Sonnenschein Nath & Rosenthal moved in from Chicago.

The ‘90s in particular saw the joining of firms looking for ways

to cut overhead and combine complementary practices. Bryan Cave absorbed

Smith, Gill, Fisher & Butts in 1995; Lathrop & Norquist merged

with Gage & Tucker to form Lathrop & Gage in 1996; and Blackwell,

Sanders, Matheny, Weary & Lombardi combined with St. Louis’ Peper

Martin Jensen Maichel & Hetlage to form the current Blackwell Sanders

Peper Martin in 1998.

None of Blackwell Sanders’ founders has survived the firm’s

nine name changes. Frank Payne Sebree also fell from his firm’s letterhead

somewhere along the way even though Samuel Sebree II—a great-grandson

of Frank—practices in Shook Hardy’s London office yet today.

Polsinelli, Shalton & Welte retains the names of its original and

still-active founders, however, and Gardiner Lathrop has held tight for

130 years.

Now Morrison & Hecker and Stinson, Mag & Fizzell have said, “I

do,” to a marriage of titans. Their planned merger will create the

second-largest law firm in Kansas City with 340 attorneys. It’s hard

to believe that the names that remain on the letterhead and the ones that

disappear will be determined by the flip of a coin, but apparently it’s

so.

Regardless of whose names appear on the office door, however, there are

partners and associates all over Kansas City today who are making a mark

on our history that will never be erased.

Return

to Table of Contents

|