Participants Include:

Donna Zimmerman, President, Southwest Johnson County E.D.C.

Mayor Carol Lehman, City of Gardner

Dr. Marjorie Kaplan, Superintendent, Shawnee Mission School District

Hon. Annabeth Surbaugh, Johnson County Commission, Dist. 3

Dr. Sally Winship, Johnson County Community College (Host)

Elaine Perilla, Board Chair, Johnson County Community College

Leawood Mayor Peggy Dunn (Panel Chair)

Johnson & Wyandotte Counties Council of Mayors (Chair)

Tom Cole, Director, Lenexa Economic Development Council

Hon. George Gross, Johnson County Commission, Dist. 4

John Ramsey, City Councilman, City of Lenexa

Michael Wilkes, City Manager, City of Olathe

Kent Crippin, Exec. Dir., Downtown Council/Former Leawood Mayor

Mayor Ed Peterson, City of Fairway

Hon. Dennis Moore, U.S. Congress

Mayor Michael Copeland, City of Olathe

Jack Cashill, Executive Editor/Moderator, Ingram's Magazine

Mayor Lori Hirons, City of Roeland Park

Ken Block, President, Block & Company, Pres.

Dr. Ron Wimmer, Superintendent, Olathe School District

John Nachbar, City Manager, Overland Park

Michael Press, Johnson County Manager

Dennis McKee, President, County Economic Research Institute

Sam Turner, President, Shawnee Mission Medical Center

Ben Craig, Chairman, Metcalf Bank

Dr. Charles Carlsen, (Panel Chair/Host)

Johnson County Community College, President

Craig Eymann, Managing Developer, Cedar Creek Properties

Dr. David Benson, Superintendent, Blue Valley School District

Joe Sweeney, Editor-in-Chief & Publisher, Ingram's Magazine

Dan Koenig, Director, Overland Park Economic Development Council

On the morning of Jan. 22, at the beautiful

Carlsen Center on the Johnson County Community College campus, Ingram’s

convened the first in its series of county-based Economic Development

forums. And what better place to start than the county of greatest growth

this past generation, Johnson County.

For the record, in the second half of the 20th century, Johnson County

transformed itself from a semi-rural exurb into a potent economic entity

in its own right and arguably one of the most powerful counties in America.

More impressively perhaps, the county managed its own growth with a keen

eye for aesthetics and accessibility. It built on the tradition of master

developer J.C. Nichols, who plotted much of southwest Kansas City and

northeast Johnson County. Without suppressing development, the county

avoided the slapdash construction that accompanies so many fast-growing

communities.

The county has also benefited greatly from the generous highway system

that serves the entire metro. In fact, despite its growth, the Kansas

City area has 30 percent more freeway miles per capita than any city in

the world.

Serving as honorary chairs were Peggy Dunn, the mayor of Leawood and chairwoman

of the Johnson and Wyandotte Counties Council of Mayors, and Dr. Charles

Carlsen, the president of JCCC and the man after whom the very center

was named. Prominent among the business, political and educational leaders

in attendance was U.S. Rep. Dennis Moore of Kansas’ Third District.

The first question was put to all the participants, and none shied away

from it. “What is the single most critical issue affecting the economic

development of Johnson County?” Dennis Moore responded first, and

he sounded a chord that resonated throughout the room.

Twenty-eight Johnson County elected officials and business professionals convened for an open dialogue in one of the county’s more progressive assemblies.

The Bedrock Issue

“One of the really critical issues,” argued Moore, “has to be education and making sure that education is properly funded.” Moore was on his way back to what he was sure would be a “contentious session” in the House, one that will be marked by “a lot of competition for limited funds.” For all that, Moore thought it critical to sustain funding for education. In his view, the backbone of the area is the “well-educated and properly trained work force for the economic engine we have here in Johnson County.”

Moore was not alone in describing Johnson County as an economic engine. Its growth in the last half of the 20th century has been consistent and relentless. In achieving that growth, Mayor Mike Copeland of Olathe described education as “our number one economic development tool.” “There is a tremendous economic benefit when public education is doing well,” concurred Dr. David Benson, superintendent of the Blue Valley school district.

Dennis McKee agreed that the county’s number one priority has to be “adequate funding for public education.” “Without education,” argued County Commissioner Annabeth Surbaugh, “everything else falls apart.” “Education and infrastructure,” Michael Wilkes summed up the county’s issues in the day’s most succinct answer.

Tom Cole of Lenexa suggested that the process is now not nearly so linear, that now sometimes the rooftops follow the commercial. He told the story of a company that had narrowed its relocation choices to Miami, Anaheim, and, improbably enough, Lenexa. As Cole noted, the “major priority” for this firm and others like it was the quality of the schools. Based on these criteria, the company chose Lenexa. Given his experience, Cole has come to believe that “maintaining our focus and emphasis on quality education” has to be the county’s number one priority.

Ron Wimmer thought the focus should be less on the dollars per se than on why the additional funding is so critical. “Money is the means by which we are able to provide services to children,” he argued. “It’s not about having money to have money.” He noted that there are challenges with young people today that require additional services and programming, and the schools need to provide them. There is also a cost involved in keeping “quality teachers” in the classroom.

To maintain market values, Ben Craig thought it critical to sell a lot harder on the idea of adequately funding public education. “It is the bedrock on which the economic development of this county rests.” Congressman Moore echoed Craig’s sentiment. “Education is the bedrock that makes Johnson County so strong.”

There was no dissent on this topic, and virtually all participants touched upon it. Given the consensus, the question was raised as to why adequate funding is even an issue.

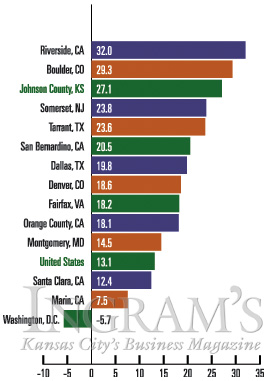

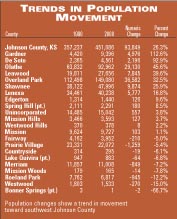

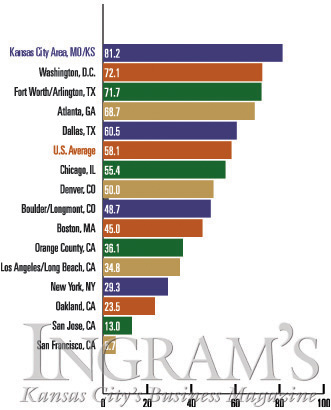

Population Growth 1990-2000 Percent Change

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and CERI

Dr. Charles Carlsen of Johnson County Community College looks on.

Leawood Mayor Peggy Dunn emphasizes the need of countywide

and bi-state collaboration.

Countyscape 2020 Vision document and its importance to the future.

Dr. Carlsen reiterates education to remain the

number one priority of Johnson County.

Educational Challenges

“No one disagrees with a good-quality education,” observed

George Gross. “The pressure is trying to balance the spending.”

Gross argued that as local governments assume more responsibilities

than they used to or even should, citizens “become accustomed to

whatever it is we’re doing” and protest loudly if ever it

is taken away.

“What is the dollar amount for quality education?” asked Ben

Craig rhetorically. “What’s our goal?”

Ken Block raised two corollary questions: “Where do you get the

funds?” and “Where’s the balance?” He argued that

now most of the revenue is derived from property taxes, but that the

benefits are widespread. “If everyone is for education,” he

argued, “everyone should pay for education.”

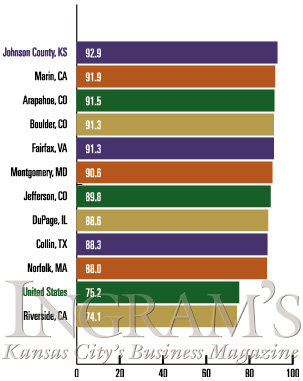

Johnson County graduates an extraordinarily

high percentage of high school students.

High School Graduates % of population 25+ with at least a High-School

Diploma

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and CERI

Kaplan also raised the issue of school districts whose enrollments are declining like Shawnee Mission’s, a problem that is aggravated because state money is allocated on a per pupil basis. “The country is filled with examples of fine suburban school districts that were allowed to run down as cities developed

farther and farther out,” Kaplan observed. “If we can turn that tide and maintain our older areas,” she added, “we will set an example for the rest of the country.” The participants seemed as vigilant as Kaplan in assuring that the schools be maintained.

One area in which the county has been notably progressive is in the area of business partnerships, particularly through Johnson County Community College. The president of the college, Charles Carlsen, re-counted how he had personally inteviewed 26 CEOs to find out what they wanted out of an educational institution.

Said Carlsen, “They are tired of hiring people with degrees who don’t have any skills.” The college

has set as its goal the identification of needed competencies and skills and the certification of these skills so people coming out of college can get a job. Twenty percent of the school’s students already have bachelor’s degrees. “They couldn’t find jobs to make a living,” noted Carlsen.

“Work force development,” in fact, is at the forefront of Johnson County Community College’s mission. Dr. Sally Winship noted that the college works hard to assess “how best we can respond quickly to all the business needs.”

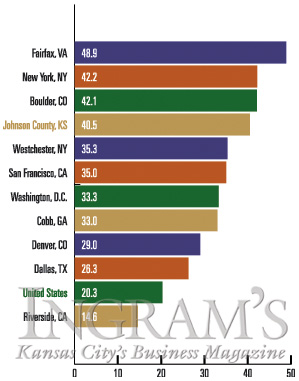

College Graduates % of population age

25+ with Bachelor’s Degree or above.

Johnson County population

has twice as many

college graduates as the national average.

Source: U.S. Census Bureau and CERI

Real estate developer Ken Block discusses the regional life sciences

movement and its tie to economic development activity.

The phrase “northeast” means something entirely different in Johnson County than it does in the rest of the metro area. Specifically, it refers to those communities that front the state line with Missouri and the county line with Wyandotte in the northeast corner of the county—Fairway, Mission, Merriam, and Roeland Park among others—attractive, viable communities all but no longer “new.”

As Roeland Park mayor Lori Hirons noted, “I think we need to be cognizant of the fact that we can’t just keep moving on and moving on and not paying attention to the community we’re moving from.”

“The pattern is set as far as new growth is concerned,” added Kent Crippin. That pattern spreads inexorably south and west, potentially leaving the north and east behind. “Those areas are really the gateway to Johnson County,” argued Crippin. “The county has to become the operating partner to assist those cities more and more. “

Fairway Mayor Ed Peterson provided the rationale for the assistance. “Why it makes sense to reinvest in this area is economic.” He continued, “We have doubled and tripled the investment in infrastructure and as a result the values have more than doubled.” “We know when we make investments in community,” added Hirons, “it impacts the homeowners.”

On the other hand, Peterson maintained, if these older suburbs are not maintained, it can engender a “creeping blight” which affects the rest of the county. “It’s a lot easier to stall decline before it happens,” added Annabeth Surbaugh, “than to recover once it’s taken place.” Johnson County Manager Michael Press confirmed the point by quantifying it, “To rebuild infrastructure costs 75 percent more than maintaining it.” Added Mayor Hirons, “We want people to not look at this as an old community.”

The challenge for a given city, as Craig Eymann posed it, “is to have the vision to realize that you are declining.” He believes the older cities have an advantage in the quest for economic development dollars, but they have to know what they are looking to do. Ken Block stated that those ED dollars are essential for the “inner municipalities” if they are to compete for projects that might otherwise be planted in virgin spaces. “We need to focus on how to coordinate the economic development efforts of different cities,” argued Block.

“There has to be a county-wide coming together for northeast Johnson County,” argued Sam Turner, president of Shawnee Mission Medical Center. For him the most compelling reason is the county’s need for affordable housing of the sort that these older communities provide. Moreover, the county could not be successful without the kind of people who would live in such housing, many of whom he employs. “If you can live in affordable housing and go to a good school district like Shawnee Mission, it is important,” he noted.

“At the same time we are trying to maintain our communities,” Marjorie Kaplan noted. “We have to have an open attitude towards change.” On the education front one feels the change most keenly when certain schools have to be closed, a move that never wins friends. Said Kaplan of change in general, “We need a lot of cooperation and understanding from governmental agencies to do this.”

Charles Carlsen cited an example from his own sphere on how change might profitably be accomplished. A few years back, three community college districts in the area offered chefs’ hospitality management programs, each of which was expensive to maintain. Instead of competing, they entered into a partnership and created one program that serves all the metropolitan area. As JCCC chairman Elaine Perilla confirmed, “To maintain the quality that we have going in here, both in education and business, we have to deal in a partnership method.”

One sensed among the participants an awareness of their interdependence and an eagerness to sustain the character of the entire county.

Roeland Park Mayor Lori Hirons discusses

the critical need of

support for the more established, yet aging communities of

Northeast Johnson County. Shawnee Mission Medical Center Pres.

SamTurner and Johnson County Community College exec.

Dr. Sally Winship observe.

Fairway Mayor Ed Peterson and County

Commissioner

Annabeth Surbaugh enjoy the light side of the assembly.

Lenexa Economic Development Director Tom

Cole explains

the county’s strength as the economic engine to the region.

Gardner Mayor Carol Lehman emphasizes the

interdependent

reliance of Johnson County to neighboring Kansas City.

The Kansas City Factor

A curious thing happened in the opening round when each participant was

asked to cite the most critical issues facing Johnson County: only one

person even mentioned the words “Kansas City.”

Tom Cole summed up the county’s relationship to the city most succinctly.

“Kansas City is not a nonfactor but over time an increasingly lesser

factor.” He spoke wryly of relocating execs arriving at the airport

and saying, “Take me to your suburb.”

He doesn’t believe this happens in cities like Chicago and attributes

it largely to the appeal of Johnson County beyond metro KC. “Our

competitors really are outside the metro,” he contended, “usually

the big cities.” He did concede, however, that “there is an

education that has to take place.” In other words, for all its renown,

Johnson County is still not Chicago.

Most other participants were more sanguine about the county’s relationship

to the city than Cole. Said Peggy Dunn succinctly, “I think that

without Kansas City, Mo., Johnson County would not be what it is.”

Carole Lehman concurred. “In southwest Johnson County, we think being

near Kansas City is a plus.” She cited the Chiefs, the Royals, the

museums and other attractions, which allow her to position Gardner as

a small, family-friendly town with big-city excitement just down the road.

“Kansas City itself,” she noted, “is part of what makes

Johnson County what it is today.”

“It is ludicrous,” argued Dennis McKee, “to think in terms

of isolating communities.” Rather, he sees area communities as interdependent.

On the marketing front, Johnson County feeds off Kansas City. And as to

work force, Johnson County draws labor from a 21-county region and is

“now a net importer of labor.” This one-time bedroom community

has come a long way in a generation.

Mayor Mike Copeland of Olathe related an anecdote that reinforced that

point. The governor was in Olathe to tour a new facility. He talked to

a number of people and asked them where they lived. The answers were Blue

Springs, Independence, Raytown—the majority on the Missouri side.

“We are what we are because of what Kansas City is,” said Copeland.

“We have to work cooperatively.”

The Housing Opportunity Index Percent of

homes

affordable for households with median income.

Source: National Association of

Home Builders and CERI

The question still loomed, though, as to which engine was pulling which. George Gross described the county as “the economic engine that drives the Kansas City area.” Kent Crippin described it almost identically. “We have to be at the table,” he argued, “because we’re the economic engine that is driving the area.”

Ken Block on the other hand described KC as “the machine that brings everyone into this area of the country.” One reads in these mechanical metaphors a sense of Johnson County as the area’s 21st century workshop with Kansas City as its glittering showroom.

“Kansas City really offers many of the things we want out of a community,” confirms Ed Peterson of Fairway, but Johnson County he sees as “the driving economic force” behind it, the disproportionate source of bi-state revenues. Like Crippin, he believes that Johnson County must participate in regional decision-making to protect its own considerable interests if for no other reason.

One of the areas where Johnson County has been at the table, affirmed Sally Winship, has been the arts. This, she describes, as “a critical area where we really work together.”

One area where the county was not at the table, countered Kent Crippin, was the debate over light rail. One sensed as the issue of metropolitan transport goes forward in the future, Johnson County will be well-represented in any meaningful discussion. Transportation is like education, said John Nachbar. “Both involve a willingness of this area to continue to invest.” John Ramsey also argued for the need to create a viable “transportation plan.”

Said Mayor Peggy Dunn, “We are not an island.”

Creating The Environment

When asked about critical issues, Dan Koenig talked about the need to create new jobs and retain existing ones and to provide “the kind of environment that allows employers to grow.” Based on the numbers, one can not deny the health of the county’s environment.

On the more superficial level, that health is sustained by a keen attention to the infrastructure and its maintenance. Many of the participants stressed the need to preserve the county’s excellent infrastructure and to balance, as George Gross mentioned, the need for growth with the need to rebuild and maintain.”

Sam Turner, who had recently moved here from Washington, asked whether there were any shortages of water in the area of the sort he experienced in D.C. Annabeth Surbaugh, who had served on the water commission, explained to him the work they had done to make sure there was not.

The Kansas City area is among the most

cosmopolitan of American cities.

Its cultural amenties, Midwestern lifestyle and affordability make it

difficult for

people to leave once accustomed to the KC-area market.

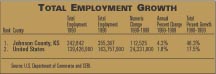

The employment growth

rate of Johnson County is nearly three times the national average.

This equates to an average growth rate of 12,503 jobs per year, or 1,042

per month.

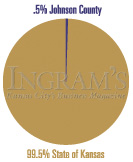

Tax Base vs. Population

1999 Assesed Property Valuation

Total Land Mass

Assessed property value of Johnson County compared

to the state of Kansas, (Top). Percent of land

Johnson County occupies in Kansas, (Bottom).

Source: CERI

David Benson suggested one other necessary

kind of maintenance, namely “the maintenance of our excellent record

in government at the local level.” He was not alone in this observation.

Good government goes a long way in suggesting why the more material parts

of the county work as well as they do.

Charles Carlsen offered a one-word answer as to why county government

is so well supported by the taxpayers: “Accountabi-lity.” The

community college, for instance, tracks its graduates to see how well

they do in four-year colleges and/or how they progress in their careers.

“I think the biggest threat to the County,” noted Carlsen, “is

complacency.”

Another factor work- ing in Johnson County’s favor is the strong

growth in the area of commercial development. As Mike Press noted, cities

cannot meet service demands “without the proper balance of commercial

and residential development.” Residential growth alone doesn’t

pay for the future.

If there is a need for improvement in government, Ron Wimmer argued that

is in the area of leadership at the state level representing Johnson County.”

He obser-ved, “People forget the impact that state has on our lives.”

Visions

Early in the session, Craig Eymann suggested the need for “a clear

vision of where we want to go as a community,” a vision that would

be documented with a clear set of goals.

One of the county’s better-kept secrets is that just such a document

exists, that it had emerged out of the “vision committee” in

1998, and that it has worked quite well. As Overland Park city manager

Mike Press noted, the publication “Countyscape” was born directly

out of this document,” a document that he considered “excellent.”

County Commissioner George Gross called it “a great vision”

and observed that it was already 50 percent implemented despite being

a 20-year plan. As Gross noted the real challenge, the real opportunity

for that matter, was that nearly half the county’s 470 square miles

was still unincorporated.

“There is life past Olathe,” Mayor Carol Lehman of Gardner reminded

the audience, referring to the still largely untapped southwest corner

of the county. “It’s a great place to live, a wonderful place

to do business.”

County Commissioner Annabeth Surbaugh remem- bered how the commissioners

asked not only for a vision statement, but also asked the vision committee

“to grade us on what we’ve done” and add to the document.

As Charles Carlsen said earlier, “accountability.”

Lori Hirons recommended that future vision statements reach out to the

municipalities to “make the document live more.” Like many others

at the table, Hirons argued strongly for the value of partnerships.

Craig Eymann recalled how much more viable the Olathe vision became when

“we got all the players that made a difference in the same room.”

Their “buy-in” made it happen.

David Benson recommended the work of a “low-profile agency,”

United Community Services of Johnson County. According to Benson, this

well established organization. “has acted as a leadership and guidance

focal point for human services.”

Late in the session the question was raised whether the participants ever aspire to make Johnson County the single best place to live in America. The question was met by an outcry of only half-joking rejoinders of the sort, “Aspire?” “I thought we were!”

Donna Zimmerman remembered how when she first moved to the area, “There was never a doubt in my mind that I was going to live in Johnson County.” She acknowledged that the entire metro area offered the amenities, but that Johnson County was where she wanted to live. “The perception from the rest of the state,” she added, “is a lot stronger than you all realize.”

“The issue,” noted Dan Koenig to a chorus of affirmations, “becomes how do you sustain it?”

Said Mayor Peggy Dunn in conclusion, “We should not take for granted what he we have here.”

CERI President Dennis McKee discusses

the critical relationship between Kansas and Missouri, and how bi

state initiatives must continue to progress for regional strength

to flourish.