Hospitality

& Tourism Progress in the Kansas City Region.

•

Figures are based on Ingram’s research, Convention and Visitors Bureau

of Greater Kansas City and Horwath Horizon Hospitality Advisors information.

(percentage increases or declines are on 1999 basis)

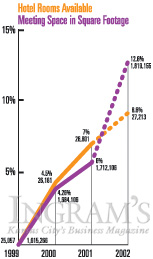

•Hotel Rooms and Meeting Space:

Square footage is based on area facilities with 10,000 square footage

or more. 2002 numbers are based on the projected completion of the Overland

Park Convention Center, Business & Technology Center Exhibit Hall

and the Sheraton Overland Park Hotel at the Convention Center.

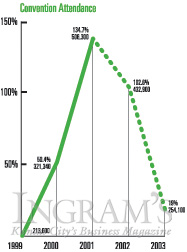

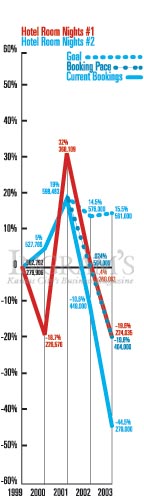

•Convention Attendance and Room

Nights #1: Numbers are based on definite and tentative bookings of groups

utilizing over 1000 peak-night guestrooms.

•Room Nights #2: Figures based

on all known groups. Booking pace and current bookings are from Nov. 2001.

Goal room nights and booking pace are based on projections currently under

development by the University of New Orleans, LA for the CVB.

The Classical Past

There is something arbitrary about picking an age and attributing golden

status to it. Such ages typically owe their status to the vision of the

people in the years that preceded them. Still, there is much to be learned

by looking at the dynamics of such periods and discerning what it is that

made them special.

Let’s call the first one the years roughly between 1898 and 1903

when KC was a shiny symbol of midcontinent progress. In the 40 years prior,

KC increased population from 4,000 to 160,000, a factor of 40.

Visitors from Paola or Platte City would experience a combination of wonders

in Kansas City they could experience in no other town between St. Louis

and San Francisco—wonders like electric street cars and elevators

and automobiles and indoor plumbing and department stores and nickelodeons.

For residents of the outlying region a century ago, visiting Kansas City

was like visiting a World’s Fair.

Shelly Schierman, president of the Louisburg Cider Mill, recalls how her

Grandpa Alexis, who was born in 1878 near Sedalia, loved to reminisce

with stories about the music scene and hustle and bustle of downtown KC

at the century’s turn.

The most telling moment in that period came in 1900 when the city’s

convention center burned to the ground just months before the scheduled

Democratic convention. In an heroic burst of can-doism, the town fathers

built a new center in the remarkable period of 90 days and gave birth

to the term “Kansas City Spirit.”

In 1903 a terrible flood ravaged the bottoms area of the city, where much

of its commercial life was rooted, and tested the city’s spirit in

unimaginable ways. More importantly perhaps, the apostles of rural electricity

were spreading out across the countryside and making Kansas City seem,

by comparison, just a little bit less lustrous than it once did.

The second golden age had more than a bit of tarnish to it, built as it

was on the ephemera of crime and corruption. During the ‘30s, while

the rest of America suffered, Kansas City was awash in cash from government

contracts and gambling fever. Musicians were recruited to keep the gamblers

amused, and the city emerged as an adult entertainment Mecca. Without

meaning to, the legendary boss Tom Pendergast helped spawn one of the

great musical periods in American history, the Kansas City jazz age.

In 1939, Pendergast was arrested for income-tax evasion, but it no longer

much mattered. The energy of the period had already been spent. The musicians

had begun to move on. Pendergast had left almost nothing on which to build,

his model holding no promise for the KC of today, though Las Vegas did

well enough by it, if Atlantic City did less well.

The third golden age deserves more attention given both its dynamics and

its relatively recent vintage. This would be the period 1972-77, according

to the Kansas City Star, the “best five years in Kansas City’s

history.”

The ‘70s, in fact, belonged to Kansas City as no decade ever has.

On Jan. 10, 1970, the underdog Chiefs of the once-scorned American Football

League rose up and smashed the Minnesota Vikings of the haughty NFC. It

was the first major championship in a city that was finally beginning

to believe it deserved one.

Extraordinary things happened in ‘72. For starters, the city unveiled

the new Kansas City International, “a jet age marvel of an airport.”

This also represented KC’s greatest single investment ever made.

That same year, the Hall family opened the Crown Center complex, the single

greatest private investment in urban redevelopment anywhere. In 1972,

the Truman Sports Complex got ready for its first game. At the time, the

twin stadiums were a national wonder. And “to help revitalize downtown,”

the city snagged an NBA franchise for downtown’s Municipal Auditorium.

Within a few years, in fact, Kansas City would be one of only nine cities

in America—and easily the smallest—to field teams in all four

major sports. Scouts. Chiefs. Royals. Kings. The Kings would play in the

new Kemper Arena. Conventions would be staged in the new Bartle Hall.

Families would flock to the new Worlds of Fun. The city had never known

such a period of substantial progress.

The wonders that came on line in the early ‘70s, however, attracted

attention by their novelty, not by their coherence. In fact, their diverse

locations would only pull energy away from the center.

“What’s missing,” argues Dan Serda, executive director

of the Kansas City Design Center and a serious student of urban life,

“is a coherent sense of the city as an urban place.”

“Kansas City’s greatest challenge,” Serda continues, “is

to remake the physical and cultural vitality of its urban fabric. This

means more than simply investing in signature projects, elite cultural

institutions, or other symbols of ‘world-class’ status. It means

clustering attractions in a synergistic density, enabling spontaneity,

and encouraging small-scale enterprise and opportunities for individual

exploration.”

Serda is a little young to remember the attraction of the early ‘70s

that accomplished almost exactly the cityscape he imagines. Slowly and

lovingly, developer Marion Trozzolo had been gathering and restoring properties

in the city’s all but forgotten market area. In 1972, that “year

of years,” he rechristened the area the “River Quay” and

opened it to the world.

Of all the attractions of that era, none injected the flavor of a big

city more powerfully than the River Quay. At its peak, it had the potential

to be another French Quarter, a spontaneous mix of arts, crafts, music,

and food. On weekend nights tens of thousands of people—from all

over the region—would flock to the Quay to get a first hand sense

of what real city life was like.

Centrally located as it was, the River Quay pulled visitors from all over

the metropolis and beyond. It was close enough to reinject life into downtown

KC and attractive enough to obliterate distinctions of race and class,

more raw in the ‘70s than now. In fact, the city’s promotional

literature from the period typically led with images of the Quay. This

was what a big city was supposed to look like.

The River Quay could have continued to prosper. There was nothing artificial

about its foundation. If anything, it proved too attractive. Rival gangsters,

keen on monopolizing the River Quay, engaged in a violent turf war and

blew half of the Quay up in the process.

This third golden age ended not with a whimper, but with a bang. Literally.

In 1977, the same year the Quay self-destructed, a Plaza flood left thirty

dead. Within a few years, the roof would fall in at Kemper.

Its heart imploded, its momentum lost, the city now seemed to a regional

visitor like no more than a series of increasingly ordinary attractions

spread throughout the area connected by a loop of interstate. The major

new attractions in the years since—the casinos, Nascar, the malls—have

only increased the sense of dispersion.

Reversing

The Trend

Bill Lucas of Crown Center believes that Kansas City can make the necessary

long-term changes to become a regional magnet. But he also knows it won’t

be easy.

“That would be a very big project,” he notes, “and it would

be very similar to the Downtown River-Crown-Plaza.” As part of this

vision, he imagines “big costly things,” including bigger facilities,

an improvement in the entertainment and tourist package, an increase in

the hotel market, and the revitalization of downtown.

Dan Serda imagines KC’s tourist revitalization on a smaller scale.

“Kansas City’s greatest strengths as a regional capital, unfortunately,

are neither particularly well understood nor often considered in packaging

by local boosters,” Serda argues. “Historically, KC has proven

fertile ground for creativity and innovation.”

Serda cites as proof the city’s numerous architectural firms, which

he sees as an outgrowth of the KC’s historic role as a center of

railroad engineering and urban infrastructure design. This, he posits,

as a “more authentic and meaningful image for KC.”

One good sign of a functional city, according to Serda, is that it presents

“informal opportunities for enjoying urban life through convivial,

organic spaces.” In this regard, KC is currently lacking, most noticeably

downtown.

Like Serda, Greg Hawley of the Steamboat Arabia Museum envisions the revitalized

Kansas City on a smaller scale. Hawley, however, is more specific in defining

where the heart of this city should be, namely the West Bottoms.

Hawley argues that we should “go back to our roots and create an

old-town atmosphere.” He envisions a “community of loft apartments,

compatible retail, and tourism that is generated from river-related entertainment,

recreational boats and luxury cruise barges.”

Hawley’s vision serves as a reminder of how the synergistic possibilities

of the “riverboat” casinos were squandered. Their disparate

locations aggravate a problem that could have been solved had the casinos

been limited to specific enterprise zones.

Doug Gamble, the vice-president of development for U.S. Franchise Systems

(Hawthorn Suites), has a unique take on the city. Although a Kansas City

native, he has lived in nine cities in the last nine years in three different

countries developing hotel properties.

Each summer, he notes, a particular city is designated the cultural capital

of Europe. “We should market ourselves,” he continues, “as

the Cultural Capital of the Plains.” In his opinion, this is how

many people in the four-state region already view us and thus how we should

view ourselves.

Gamble cites as examples Shakespeare in the Park, Friday-night gallery

openings in the Freight District, Royals games, and more. “All contribute

to our already strong regional draw.” The secret to success, he believes,

is better, more coherent marketing.

Shelly Schierman, president of the Louisburg Cider Mill, believes that

the city should “continue to play up the “Heartland” card.

This would include promotion of the city’s “central location,

easy access, and family values.”

Schierman has reason to believe that this card has increased after Sept.

11. As she says of the Cider Mill, “Retail has been stronger than

ever.” Schierman attributes this to a more regionalized focus on

travel and a renewed interest in heartland values.

Although business at area hotels softened after Sept. 11, Bill Lucas notes

that “we are faring better than other cities we are aware of.”

He attributes KC’s relative stability to its “cost of air fare

and a value-driven location.” In fact, Lucas sees the city’s

“price-value relationship” as its greatest asset.

The

There There

Culture critic Gertrude Stein famously slighted the city of Oakland, CA,

with the cutting phrase, “There is no there there.”

Kansas City seems to face a similar dilemma, namely “Where is our

there?” Where are the “convivial, organic spaces’ that

define the city and make it memorable? In 70s, River Quay served that

function. Before its slow collapse in the 1960s, downtown served that

function. Now many people, Mayor Barnes of KC included, envision the south

loop area, the area between downtown and Union Station, a district unpopularly

referred to by the mayor as SoLo, as the logical successor.

On this point, however, there is no consensus among our respondents. Bill

Lucas looks to the entire stretch between the Plaza and the River. Greg

Hawley focuses on the West Bottoms.

Doug Gamble sees the most likely site for such an environment as the South-west

Boulevard area, the city’s historic Mexican community. For these

same spaces, Dan Serda looks to the “the quality places, like the

Plaza and Westport that already exist and convey a sense of the possibilities

in store.” Shelly Schierman sees no particular need for such a place

at all.

For Kansas City to reinforce its natural position as a regional tourist

Mecca, someone or some group of people must squarely define where is our

“there.”

The large hospitality features that Lucas envisions can coexist with the

smaller, more spontaneous attractions that Dan Serda and others envision.

But for a given area to attain critical urban mass, for it to define KC

in the eyes of the traveler, there needs to be some consensus on where

that area will be.

The virtues of KC are undeniable. As Bill Lucas observes, “It is

a great place to live and raise a family.” But, as Lucas adds wryly,

“That does not necessarily mean it is a great place to visit.”

The potential is there, however. All that is needed now is the will to

develop it and the leadership to make it thrive.