Back in the Cold War days, the concept of mutually assured destruction provided a certain measure of stability between the United States and Soviet Union. As long as your opposite number wasn’t a total whack-job, you could achieve something approximating peace.

Banking is a business, not a national-security strategy, but Tom Metzger also understands the importance of having competitors who live in the real world. He and his partners from Boston-based National Bank Holdings, who acquired both Bank Midwest and Hillcrest Bank last year, chose to enter a Kansas City market that was amply stocked with banks.

There were good reasons for that, beyond the economic fundamentals of the deal, Metzger says.

“From a competitive point of view,” he says, “we saw the competition here as very rational—whether it’s Commerce, UMB, Bank of America, US Bank—they’re all rational competitors. In a lot of other markets, there are some banks that have gotten pretty irrational on structure and pricing. It doesn’t make sense for the long haul to compete with somebody who’s irrational in that regard.”

For that reason, for the region’s sound economic fundamentals and owing to changes coming from a hyperactive regulatory gland in Washington, Kansas City-area consumers can expect to see continuing changes in the banking landscape. With NBH already having acquired two of the region’s 10 largest banks, much of that change will likely play out among mid-size and small banks, banking professionals say.

In the year before they were acquired, Bank Midwest and Hillcrest were two of the three Top 10 regional banks that posted losses, and the fresh capitalization injected into this market by NBH is expected to solidify the roster of bigger players for the time being.

But looking back from where we stood at the close of the 20th century, the change among players here already has been considerable.

Changing Landscape

In 2000, you would find on a roster of the region’s 25 biggest banks names like Gold, Firstar, Bannister, Jacomo, Guaranty and First National of Missouri.

You won’t see those names today, but that doesn’t mean their forerunners aren’t out there somewhere in the banking sector ether. They and many other banks have evolved—merged, acquired or been acquired, sold off divisions or changed ownership. Big banks have taken over operations of smaller, struggling organizations. Smaller banks have bulked up through aggressive acquisitions. And regardless of size, even healthy operations have joined forces to capitalize on improved efficiencies and broaden service lines.

Size was no protection against that change, as the NBH acquisitions demonstrated. The forces at work, says Mike Lochmann, a lawyer specializing in banking law for Stinson Morrison Hecker, are both national and local in scope. And they’ll continue to relay the playing field for regional banking for years to come.

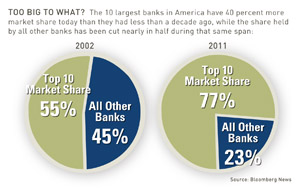

“I think there will be a dramatic consolidation in terms of independent banks,” Lochmann said. “There will be fewer banks in the country as a whole, and fewer by name in the local market.”

For individual customers and business clients, he said, plenty of choices would remain, and the consolidation could even pay off with more types of banking services and more access to those services. But, on a national scale, “will we have 2,000 to 4,000 fewer banks? And of those left, how big can they get?” Lochmann said. “I hesitate to think that’s good for the economy.”

He cited several reasons for that: “Small community banks that have been there for 50 or 100 years know all the businesses and the players and can underwrite not only the financials, but the integrity and roots of the owner: Is this somebody who will put money back into the business to make sure loans get paid, or skip town when things go bad and say, ‘Here’s the keys.’ They are right there in church, in the Kiwanis club or at Little League with their customers.

“They know these people in a way that the out-of-state megabank doesn’t,” Lochmann said. “So in underwriting small business loans, I think smaller banks may have some advantages.”

Growth at the Top

One notable development in the banking market here is the growth in assets overall—especially among the biggest players.

Among the banks operating in the Kansas City MSA in 2000, combined assets were $26.4 billion according to the Federal Deposit Insurance Corp. Inflation measures may be a crude tool for banking comparisons, but $26.4 billion then is equivalent to about $33.1 billion today. But the region’s banks have blown well past that level, with combined assets of $42.3 billion—2.4 times the inflation rate.

And chief among them is Commerce Bank, which owns the biggest piece of banking assets in this region. Since 2000, it has nearly doubled that figure, from $9.34 billion in 2000 to $18.34 billion in 2010. That works out to an increase of nearly $2.95 million in asset growth every banking day since 2001.

It was achieved, says Commerce Bank President Kevin Barth, largely through organic growth, capitalizing on changes at other banks to draw in new customers and their accounts.

“What’s really helped us the last 10 to 15 years was that, as a lot of other local and regional competitors sold out to national or money-center banks, we were able to pick up a lot of market share with retail and commercial customers,” Barth said. In checking accounts alone, he said, the bank had added roughly 5,000 cus- tomers a year since the nation’s financial crisis erupted three years ago.

UMB, the other half of the extended Kemper family’s banking empire, surged from $6.7 billion to $10.69 billion in assets—an increase of nearly 60 percent. Like Commerce, much of that growth was organic, but the holding company that owns UMB is growing in other ways. Through its Scout Investment Advisers division, it has been on an acquisition spree over the past year, more than doubling its overall footprint by expanding with both individual and institutional investment reach.

Scout entered 2010 with $8.3 billion in assets managed before the acquisitions of Prairie Capital and Reams Asset Management. Overall, UMB Financial Corp. now encompasses more than $28 billion in banking assets or wealth under management, said CEO Peter deSilva.

Between them, the top two banks have increased their share of the overall market in terms of deposits, according to FDIC, but not sharply. With 11.64 percent of those deposits in 2010, Commerce has moved up from fourth place a decade ago to overtake UMB (now at 11.07 percent), the market leader in 2000. Now, as then, Bank of America is the only other double-digit force in the KC MSA, most recently at 10.12 percent.

(...continued)