HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

There is a memorable line early in the movie Miracle, the 2004 film that chronicles the gold-medal journey of the 1980 U.S. Olympic hockey team.

Told by his assistant coach that the squad was missing some of the best available players, Coach Herb Brooks (portrayed by Kurt Russell) fires back: “I’m not looking for the best players—I’m looking for the right ones.”

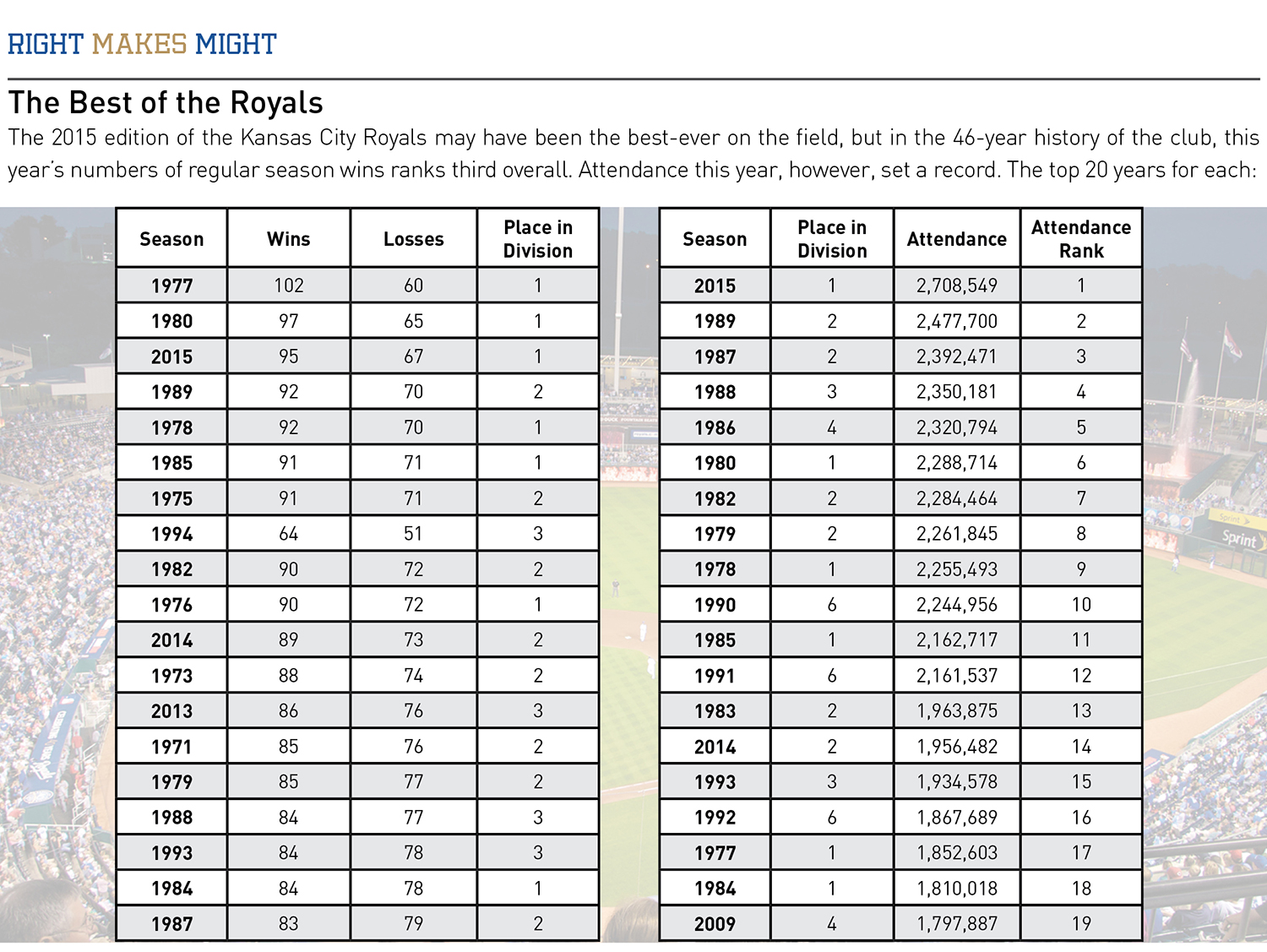

That’s a lesson for managers across every profession, and in our town, we’ve seen evidence of its validity in the championship run of the 2015 Kansas City Royals—a team of great synergy, constructed with patience, diligence and character.

Assembling and managing the right team in any business is not easy. Professional sports make it even more challen-ging. A collection of banks or a row of restaurants can all be profitable and dub their year a success. But in sports, only one team looks back on its season with complete satisfaction; everyone else in the league will feel as if they have failed. And all decisions are made in a fish bowl, intensely scrutinized by the media and a public that demands instantaneous gratification.

That’s what makes the story of this year’s Royals so compelling. It was a long climb from the abyss, but it is a case study in effective management.

I have watched the Royals with passion since their first game in 1969, and enjoyed their ascension from expansion team to the 1985 World Series championship. Through their first 20-plus seasons, they were arguably the most successful expansion franchise in baseball history. Then owner Ewing Kauffman died, George Brett retired and the labor dispute of 1994 altered the economics of the game, to the detriment of small markets.

Kauffman developed a complex succes-sion plan to ensure that the team stayed in Kansas City, but it took six years before Walmart executive David Glass purchased the club. In the interim, the team was run by a committee on a shoestring budget. Effectively they were ownerless and rudderless, and their decline on the field was precipitous.

Beginning in 1995, they posted a losing record in 17 of 18 seasons. There was a fluky winning record in 2003, followed by 403 losses over the next four years. Fan interest was at low ebb. It usually took a Fireworks Friday or a Buck Night to draw a sizable crowd to Kauffman Stadium, unless the visiting team happened to be the St. Louis Cardinals or New York Yankees. On those occasions the number of opposing fans approached or even exceeded those who were root-root-rooting for the home team.

The Royals did supply some comic relief. There was a 19-game losing streak in 2005, when the team’s national persona was as the butt of a Jay Leno joke. There was a home match against Cleveland in August 2006, when Kansas City scored 10 runs in the first inning—and lost. The blooper reel was longer than the highlight film. My particular “favorite” was when two Royals outfielders converged on a two-out fly ball, and then jogged in step toward the dugout as the baseball dropped untouched behind them.

During his first six years as owner, Glass bore the brunt of the fans’ wrath as the club’s payroll hovered near the bottom of the industry. But he began to initiate change in 2006 when he hired Dayton Moore from the Atlanta Braves. Moore was promised more resources and given complete control of all baseball operations. Glass made a commitment to increase player salaries, but signing the richest free-agent players was not possible or practical in a smaller market. Building a champion required a plan rooted in scouting, drafting, player development and an investment in talent-laden Latin America, where the Royals previously had minimal presence.

But winning baseball was still not forth-coming. After 100 losses in 2006, the Royals lost at least 90 games in five of the next six seasons. Moore’s first hire as manager, Trey Hillman, appeared overmatched in his first big-league managerial stint. High draft picks had not developed at the rate of other teams’ prospects, and other small-market franchises were building contenders. Fans grew impatient as the Royals’ playoff absence remained the longest in North American sports.

Soren Petro, Kansas City’s long-time sports talk host on 810 Radio, remembers the frustration.

“If you wanted to light up the lines at the station, you mentioned Dayton Moore’s performance. There were a lot of vocal fans who said he should be gone. I was saying he should be given time to produce a winner by 2013 and a playoff-caliber team by ’14, and I took a lot of heat for that.”

At 86-76, the Royals finally posted a winning record in 2013 but fell short of the post-season for the 28th consecutive year. When the club meandered through the first half of 2014 and stood at 48-50 in late July, it appeared the playoff famine would continue ad infinitum.

Then a 41-23 record over the remainder of the season earned the team a wild-card berth and ended the drought. The Royals staged an improbable comeback to defeat Oakland in that one-game playoff, and swept both the Angels and Orioles on their way to the World Series. There they fell agonizingly short—by 90 feet in Game 7—after a freakishly historic pitching performance by the Giants’ Madison Bumgarner.

One year later, the Royals sit on top of the baseball world. After the national media relied on mathematical models to forecast a losing record for 2015, the Royals stormed to the A.L. Central Division title, followed by an unprecedented run of come-from-behind victories in the playoffs over Houston and favored Toronto. In the World Series, they disposed of the New York Mets in a riveting five-game set that featured even more historic comeback heroics.

The team had progressed from the laughing stock of baseball to win its first World Championship in 30 years. The transformation envisioned by Glass and Moore almost a decade before was now complete.

Most observers point to that 2014 wild-card game as the turning point. However, looking at one night as the pivotal moment after years of losing is too scripted. The change was more gradual, and required the embracing of a plan decried by many when the results weren’t immediate. And it meant finding the right people and letting them do their jobs.

Petro says that few still saw this type of success coming.

“Around 2012, we had (former Reds’ general manager) Jim Bowden on the show. He said the Royals had the good, young pieces in place, and that eventually they would be going to the White House (as World Champions). Wow, we thought, that’s crazy. There was no history with this regime to see that.”

Moore could not build the team the way it was done by Kauffman’s front office in the 1970s. An experienced superstar of Brett’s caliber would not be affordable today in a market the size of Kansas City.

Don Pfannenstiel is an experienced Royals observer who covered the team for The Examiner in the early ’80s and was an official scorer at the 1980 World Series. He sees a fair amount of variance in the makeup of the two Royals championship squads.

“The obvious difference is that there is no real superstar today. Those 1980s teams were led

by Brett, and there were other great players like Amos Otis, Hal McRae, Frank White and

Willie Wilson. Top to bottom, this year’s starting lineup has more depth, is more complete.”

Why? Because Moore sought value throughout the roster. While other teams paid a premium for sluggers with high on-base percentages, he pursued speed, athleticism and defensive prowess that fit the spacious parameters of Kauffman Stadium. He focused on building a deep bullpen, which could be done more economically than investing in top-of-the-rotation starters.

Moore added to the scouting staff and scoured Latin America for players. When needed, he would supplement the roster with prudent free-agent signings. And in every instance,

he looked for personnel with the mental make-up to be the right “fit” for the organization.

“Don’t forget,” adds Petro, “that David Glass also ramped up the payroll.”

Though not every decision was the right one and the playoffs remained elusive, Moore stuck to his convictions and quietly took the steps needed to construct a winner. After Hillman was fired as manager, Moore turned to Ned Yost, who had been a coach with the Braves at the same time Moore was in their front office. Yost had previously managed in Milwaukee, where he was fired with 12 games left in the 2008 season despite the Brewers’ being in a playoff chase. He came with a reputation as a good developer of young players, but his ability to win a championship was questioned.

Consistent with the organization’s values, Yost has stated publicly that he tries not to over-manage, that he lets his players know their roles and lets them do their jobs. He was mocked at times for his curmudgeonly statements to the media and for his in-game decisions, but there was no doubting his character and his ability to cohesively handle a group of young men from very diverse backgrounds. He also learned from his experience and softened his approach. He was willing to endure some mid-season losses in order to build a winner over the long haul, so he stuck with young players who were struggling, and managed his pitching staff accordingly.

Two years ago, some fans were ready to run Yost out of town. Today he is a cinch to become a member of the Royals Hall of Fame.

Yost’s staff includes two former major-league managers and an experienced collection of coaches. The Royals are exceptionally organized in their advance scouting and pre-game preparation. Cases in point were two aggressive base-running decisions in the decisive games against Toronto and New York.

Each resulted from studying the opponents’ defensive tendencies and deficiencies, and each resulted in a run that ultimately tipped the game, and the series, in Kansas City’s favor.

Coaching and managing will only carry a team so far, however, because ultimately, it is the team on the field that must execute. Once again, it came down to finding the right people, patiently developing them and letting them do their jobs.

Alex Gordon (2005), Mike Moustakas (2007) and Eric Hosmer (2008) were chosen among the first three picks of their respective drafts—but each was considered a potential bust at some point early in his career. Moore and Yost stayed with them, and now the trio performs at an All-Star level.

After the 2010 season, Moore traded former Cy Young winner Zack Greinke to Milwaukee in a multi-player deal that re-turned shortstop Alcides Escobar and a minor-league outfielder named Lorenzo Cain. Both are now All-Stars and have been the MVPs of the last two League Championship Series. Greinke, who didn’t want to be part of another rebuilding process, remains an elite talent but has yet to pitch in a World Series.

Moore took a huge risk before the 2013 season when he acquired pitchers James Shields and Wade Davis from Tampa Bay in exchange for four prospects, including Wil Myers, Baseball America’s Minor League Play-er of the Year. Critics railed, because Myers was seen as a rising star under club control for several years, while Shields’ contract would only keep him with the team through 2014. But before he left Kansas City, Shields brought an exemplary swagger that taught the younger players how to win, and Davis has developed into baseball’s most dominant relief pitcher.

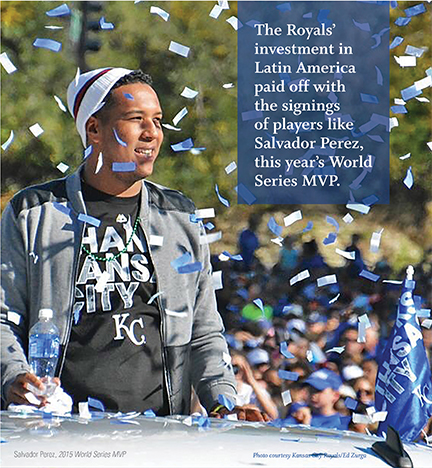

The Latin American investment paid off as well, yielding pitchers Kelvin Herrera and Yordano Ventura, and above all, catcher Salvador Perez, a three-time All-Star and the 2015 World Series MVP who was signed in 2006 as a 16-year old from Venezuela.

Before the 2015 season, Moore added free agents who ultimately played key roles in the championship run—among them Kendrys Morales, Chris Young, Edinson Volquez and Ryan Madson. At the time, the acquisitions were greeted with indifference and even scorn by the baseball pundits, but Moore saw value in their skills as players and as individuals. His evaluations proved correct.

And finally, when the Royals were just a couple of missing pieces away from assembling a true championship roster, Moore again dipped into the deep talent he had nurtured in his minor leagues. He traded prospects for pitcher Johnny Cueto and the versatile Ben Zobrist—the first time the Royals had been a real player in acquiring proven stars before the mid-season trading deadline. The acquisi-tions were made solely with the post-season in mind, and both players made significant contributions when it counted most.

“The team didn’t stand pat,” says Petro.

The Chicago Cubs have not won a World Series since 1908, and the Cleveland Indians since 1948. Two franchises—Seattle and Washington—have never even played in a Series in their combined 94 years of existence. The wealthy Los Angeles Dodgers haven’t been to the Fall Classic since 1988, and they failed again this year with an all-time record payroll of $272 million. It’s not easy to reach the World Series at all, much less in consecutive years.

According to Sports Illustrated, the Royals had baseball’s 17th-highest opening-day payroll, but they won a championship based on deft management, character and foresight, with a style of play that valued speed, defense, contact hitting and a shutdown bullpen.

“The game had built itself in a direction that relied less on scouting, and it left an opening for the Moore approach to return to those roots,” says Petro. “I think Dayton always understood what baseball had forgotten. He also recognized the value of the relief pitcher and the athlete who can run and play defense.

“There are 27 outs in the game, but with great defense, the Royals take some outs away from the opponent, and with speed and contact, they steal outs offensively.”

Have the Royals found an innovative way to win that will be copied by other teams in the future? Perhaps. But it will be hard to duplicate the intangibles of a having the “right” people, who set a record for post-season resiliency.