HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

Somewhere out there is a recent retiree who was born on Jan. 1, 1946—the dawn of the Baby Boom generation. In the history of American investing—mass investing, anyway—very few have been in as fortunate a demographic, in as rewarding an investment climate, as this individual.

“What’s changed is the diversification. ... We’re going to see more folks in alternative investments.” — Brian Leitner, chief practice management officer Mariner Wealth Advisors

He or she was just 34 in 1980, when the Internal Revenue Service adopted what’s now known as section 401(k) of the tax code, allowing individual investors to set aside pre-tax savings toward a retirement plan. Soon after that, on Aug. 13, 1982, the Dow Jones industrial average jumped 11.13 points—up 1.4 percent—to 788.05.

It wasn’t a huge gain in percentage terms, but it marked the start of the great bull market of the 1980s and 1990s, and over the course of 20 years, the Dow returned a gain of more than 1,000 percent.

Then after the dot-com bust of 2000 and post 9/11 jitters, all the way through the Trump Bump, the patient Boomer investor was rewarded as equities reached historic highs once more, just as the Golden Years beckoned.

It’s hard to imagine another generation falling into that kind of blessed investing environment. The consequences of that boom—not all of them good—will be with us for decades to come.

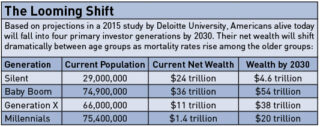

The downside? Far too many Boomers missed out on the rocket ride; most still haven’t saved enough to fund the retirement lifestyle they really want. Their reliance on Social Security will pose federal funding challenges for at least another generation. The upside of Boomer success? Their age cohort overall is the wealthiest in human history, with aggregate assets estimated at $30 trillion, and potentially swelling to $54 trillion by the time the last of them have passed their estates on to their heirs, according to projections from Deloitte.

That, says Vince Morris, president of the financial-services division of Bukaty Companies, represents “a huge transition, the largest ever in the history of the world. And then you have Millennials coming and topping the Boomers in terms of demographics and sheer numbers of people. It’s going to be a huge sea change.”

That sea change will usher in a new era of opportunities for wealth-management companies, to be sure; in combination with projected increases in household wealth, $150 billion and $240 billion in wealth management fees could be up for grabs by 2030, Deloitte says. But it also represents profound change for the other generations still investing—the remnants of the Greatest and Silent Generations, the back-half Boomers who are still a decade from retirement, a Generation X cohort that appears less risk-tolerant, and the Millennials who have already taken the crown from Boomers as the biggest generation in U.S. history.

To assess those challenges, Ingram’s sounded out executives from some of the region’s biggest wealth-management firms. What they had to offer was a generation-by-generation peek at challenges, opportunities, trend lines and warning signs that will play out over the next half-century, until the last of the Millennials, now in their late teens, reaches retirement age.

Baby Boomers

There are older and younger generations, but Boomers are first in the minds of wealth managers who are following the money. Already, they are distinguishing themselves from investors of previous generations.

“We are not seeing Boomers pursue preservation and income to the degree that previous generations may have, and for good reason: they can’t afford to,” says Emily West, who leads the wealth planning group for FCI Advisors. “The Boomers are the first generation to retire largely without defined benefit plans,” she said, and that, “combined with increased life expectancies and historic low interest rates, is a radically different landscape in which the average retiree can’t afford to forgo the pursuit of growth in their portfolios.” Result? A good deal of angst among that cohort.

But Boomers overall have helped change investing, said Brian Leitner of Mariner Wealth Advisors, and one way has been through their demands for more tools. “What’s changed is the diversification,” he said. An environment of stocks, bonds and cash, with large-cap blue chips driving most portfolios, has given way to a new investing ecosystem. “That’s changing today, and we’re going to see more folks in alternative investments,” Leitner said. The other consideration for Boomers, especially those looking for less risk, is that interest rates aren’t likely to provide much encouragement, even with recent bumps up. “Rates have been low for a while, and they’re likely going to continue to be low. What does that mean? If you need a cash income, you’re not making any money.”

A consequence of that, he said, is that investors with shorter-term horizons and less margin for error are “going after the divided-paying stocks, largely blue chips. They’re chasing yield, and taking on too much risk.”

Given that, says American Century’s Jay Hummel, it’s hard to help steer them toward success. “It’s hard to get them to understand that they are taking more risk,” he said. “Many need to, because it generates their nest egg and they need the income. But they’re focused on generating, not on the risk.” It doesn’t help, he said, when cocktail-party conversations about investment returns invoke payoffs of 10 percent or more compared to a client’s 7 percent, without taking into account the factors that could have produce the higher return—such as greater exposure to market volatility.

Another concern for Boomers, he said, is that 20 percent of those who are married have at least eight years difference in ages. Combined with the seven years that women generally outlive men, people in that cohort need to plan for one person often outliving the other by 15 years—or more.

Jim Williams, chief investment officer for Creative Planning, noted another factor for Boomers. “As they transition away from the work force, many do so without the pension income that the generation before them often received,” he said. “Their portfolio is likely the sole source of maintaining their financial independence. “

For many, that means looking at avenues to drive an income stream—dividend-paying stocks, fixed-income investments or alternative, income-producing investments. “The fact that company-provided pensions are less common, and investors are more dependent than ever on their portfolios for their financial independence, leads to more focus on wealth preservation and income generation than previous generations,” Williams said.

Philip Sarnecki, managing principal at Northwestern Mutual’s RPS Financial Services, said his office is also seeing long-term care and the rising cost of care in general as investment challenges.

“My intuition would tell me they are not moving from wealth aggregation to wealth preservation and income generation the way previous generations have,” he said. Boomers are more comfortable with the markets, having ridden out downturns and profited from the ensuing rallies.

Rather than a major shift in asset allocations, West said, “the real shift will be in who Boomers trust to manage their assets, with many seeking a professional adviser for the first time in their lives.” That, she said, would shift the industry as firms are sought out for their objective advice, communication and transparency.

In any case, Leitner says that when the asset allocations come, another effect will be setting in. “A lot of money going to be changing hands. Some is going to be pulled out of 401(k) and IRA plans or out of market.” Will that be enough to affect market directions? “I would argue that it’s just the circle of life,” he said. “If you’re 70 years old and take it out, what would you do with it? You’re going to spend it. Likely on food, healthcare, housing and additional expenses that, frankly, you’ve never had before. I think that will go back into companies and the economy.”

Dana Abraham of UMB Private Wealth Management also noted the differences in Boomer retirement behaviors, “which means they are not likely to modify their asset allocation en masse,” she said. “With a longer life expectancy, and the fact that they may spend one-third of their lives in retirement, they are more likely to retain their equity exposure to ensure their savings continue to grow and keep pace with inflation.” Because of that, she believes, any decline in demand for equities because of a Boomer selling exodus should have a nominal impact on the stock market.

The Silent Generation

There’s a reason why the cohort between the Greatest Generation and the Baby Boomers is known as the Silent Generation—they were too young to fight in World War II, and didn’t make headlines during the Vietnam War the way their far more numerable counterparts did. But some attention should be paid. By Deloitte’s estimates, the Silent Generation—with considerably less longevity than the Boomers—is sitting on even more combined wealth on a per-capita basis: A total estimated at $24 trillion.

“I believe this transfer of wealth could very well become the catalyst to change how advice is provided,” said Williams. Because many of Creative Planning’s client relationships are multi-generational, he said, they encompass the entire spectrum of the family’s financial situation. “But the majority of investors who receive advice, receive it in a fractured format across multiple parties,” he said. “When wealth is transferred to this new generation, it will likely fuel a re-evaluation from beneficiaries,” he said.

They will be looking for transparency, lack of conflicts like proprietary funds, broad expertise, access to alternative investments, a comprehensive approach, and in-house professionals from the ranks of certified financial planners, CPAS, lawyers and others. “For those large firms or small firms unable to adapt to this new environment, we could see these firms go the way of the dinosaurs,” Williams said.

That generation also presents something of a shift in the way firms deal with clients—they are among the oldest members of families who receive guidance as groups, Abraham said. But “although different generations face many of the same issues, they approach these issues in very different manners,” she said. “By knowing each generation of a family relationship, we can create a customized solution that meets the needs for all of the generations involved. This process takes time and the dedication of resources in order to know and understand our clients’ stories.”

West said she had a soft spot for this generation in particular. “In contrast to the Boomers, most of these folks did retire with a traditional pension; they also tend to live simply, having come of age in the wake of the Depression and throughout World War II,” she said. “Consequently, we see the transfer of assets they have accumulated making a significant impact on the retirement plans of their heirs. This is yet another area in which good

advice—for both parties—is so critical.”

Generation X

Like many of the Boomers ahead of them, Generation X has its own set of challenges, advisers say.

“I think that a majority of Gen-Xers have not saved enough money,” said Sarnecki. “Unfortunately, as they start pushing into their 50s, they find that they are rapidly running out of time and will have to save money faster. Simply put, they do not have time on their side.”

That’s where current market valuations, sitting at record highs, become a concern. After the 50 percent decline in the Dow in 2008-09, investors needed returns of 100 percent on their balances just to get back to even.

What’s that look like in real life? From a peak above 14,000 in October 2007, the Dow needed nearly 5 ears to return to that point. For many investors, a recurrence now would present a formidable obstacle. They don’t have five years to spare.

“The concern with market valuations is that if it goes down, is stagnant or does not continue to grow, Gen-Xers may not get the type of returns that are needed to build the wealth they want in order to achieve the retirement they’ve imagined,” said Sarnecki. “If they’re in their 50s, and the market is growing at a slower percentage than thought, Gen-Xers could become faced with some big challenges.”

It’s no secret, said West, that many Xers are underfunded for retirement. “We see many clients really hit the gas on retirement savings in the last 10 to 15 years of their careers, making up for lost time,” she said. “Pursuit of growth is a tool that can be used strategically, but it shouldn’t be the only one.” Much of their success, she said, will come down to things investors can control: how much they save, how much they spend.

As a Gen Xer himself, Morris knows that many of his peers will benefit from the generational wealth transfer coming from the two older cohorts. That, however, isn’t a strategy that can be broadly applied. Especially, he said, because they tend to be more risk-averse. “If anything has caused them to be behind,” he said, “it’s the over-conservativeness from living through two downturns. Add in job displacement, and, again, the downturn has caused them to be behind from a savings perspective.”

More discouraging, he said, “was that many have seen their Boomer parents work into retirement. It’s really predominant on their minds.”

The Millennials

With the oldest of them now in their mid-30s, it is time, suggests Philip Sarnecki, for Millennials to bone up on the fundamentals of wealth accumulation. “I have seen that Millennials prove to be less sophisticated in their investments, while also being way more risk averse,” he said. On top of that, “Millennials are much more focused on using wealth for philanthropic purposes.”

Those two goals will be in conflict with each other if the desire to make a philanthropic mark isn’t matched with a corresponding portfolio.

At this stage, they’re also more likely to be going it alone, other advisers say. “Millennials are much more prone to do it with self-service, given the tech tools that exist,” said Vince Morris. “But they still want financial advice through human interaction. Whether that’s a chat via online or by phone, most of what we see from the robo side have adopted some form of human interface. Ultimately, that’s where this battle goes.”

Fortunately for many, he said, more companies have embraced auto-enroll 401(k) plans, putting young workers on the trail of saving right out of the career gate. “Those are creating an environment where they’re getting used to saving earlier,” he said. “A lot of Boomers didn’t have that, but it makes for a smarter consumer.”

Also going for them is the range of tools, which continues to expand. As Jay Hummel noted, “they have more choices than any generation before them. What concerns me most is that this generation has watched their parents or grandparents lose a significant amount of money in downturns. While they may have a large allocation of cash as a generation, they also have a much greater fear of investing than any other generation.”

Beyond the bear markets young investors have seen, said Jim Williams, there has been the impact of the real-estate crash a decade ago, which cost many families much of the equity in the biggest investments they own. On top of that, he said, “they are often coming into a workforce saddled with student loan debt, and unable to consider home ownership due to the stricter lending requirements.”

Further, they graduated into one of the toughest job markets of the past half-century, and their early earnings trajectory has suffered as a result. “In general, these events have imbued Millennials with a fear and skepticism regarding investing, as well as their future,” Williams said. “This skepticism translates into an interest in investments that will have a positive impact on the future, focusing on socially conscious or environmentally conscious investments.”

But working for them more than any other generation, of course, is the distant time horizon. “It’s still early days for Millennials,” said Emily West. “On the high end, they are in their early 30s; they graduated into a challenging labor market, many are carrying student debt with them.”

Given the headwinds they’ve faced from a wealth-accumulation standpoint, she said, “it will be interesting to see how they evolve as they become more established. How much of the attitudes and preferences we see ascribed to them are really generational vs. being symptomatic of their phase of life? So much is still changing with this age group, it’s really too soon to say.”