HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

In June 2014, as the U.S. military was in full drawdown mode following the phased withdrawal of forces from Afghanistan, a palpable sense of concern over the future of displaced veterans was settling in over Kansas and Missouri.

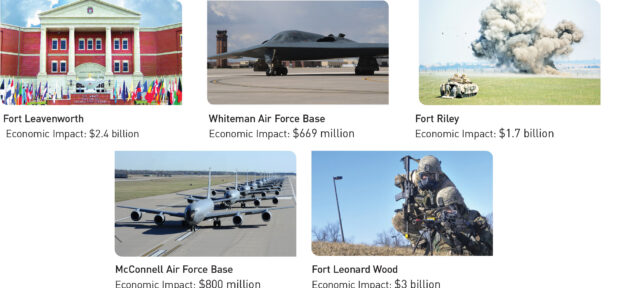

With five major military installations across two states, the Kansas City region is well-positioned to benefit economically. But there’s more to their presence here—much more— than the size of their payrolls.

At that time, the nation’s official unemployment rate was still hovering north of 6 percent. The U-6 unemployment rate, considered by many economists a more reliable indicator of the job market’s challenges, was more than twice that figure, 12.4 percent. Both offered strong indications that anyone looking for work, even well-qualified individuals, was staring at some long odds.

Since then, many of those veterans entering civilian life—and the numbers suggest their ranks could have been more than 1 million strong—have been able to find new careers.

But with the overall ranks of the nation’s military thus depleted, the bi-region has been exposed to another end of a whipsawing effect: Fewer military members, by definition, means fewer people coming into this region and, potentially, deciding to make it home. And it would mean a reduced economic footprint for the five major installations strewn across Kansas and Missouri.

The good news for regional business, however, is that if that footprint is smaller, it’s not much smaller. Think about it in these terms: Even after staffing reductions at regional Army forts and Air Force bases, how many businesses in the two-state region account for more than 53,000 jobs (civilian and active-duty)? How many can still demonstrate an aggregate economic impact of well more than $8.5 billion in this region?

The latter number is particularly significant for businesses, from which the bases buy a long list of materials and services, including food, water and power, information technology, construction and contracting services, and much more. But there’s another asset, one almost impossible to price, that the bases provide: Talent.

When service terms are over and careers end, many of those stationed in this region decide to stay here. And they do so affirmatively—in many cases, they’ve seen much of what the country has to offer on varied base assignments, and what the world has to offer, via deployments overseas. When they pick Kansas City, this region gets highly trained, highly disciplined critical thinkers who understand the value of both innovation and the importance of chain of command.

In the aftermath of the drawdown, a number of companies and concerned retired officers moved on different paths to address the needs of veterans. At Fort Leavenworth, the Center for Transitional Leadership took an elevated role in assisting detached servicemen, particularly officers, with finding new lines of work. Corporate executives with military backgrounds helped ramp up the Kansas City Veterans Coalition, providing transitional assistance, mentors and other aide. Even higher education got on board, with programs like the Military Transition Certificate being set up at the University of Kansas.

The latter, said program director Mike Denning, is a 12-hour certification “that can be stacked onto any type degree, undergraduate or stand-alone, designed for veterans to help them use and translate the skills they learned in the military and give them the confidence to apply during the interview process.”

That, he said, has enabled graduates to take their leadership skills—which don’t always align neatly between military and workplace applications—into new settings. “That’s just one example of how education has tried to help that population of veterans finding meaningful employment,” Denning said.

Among other changes affecting military installations has been the Pentagon’s decision to create Army University and make its headquarters at Fort Leavenworth, with a goal of creating a unified university, much like a state university system, within the Army’s Training and Doctrine Command. More than 100,000 active-duty personnel have taken classes through AU since it was launched in June 2015.

This region also benefits from what might be considered a hidden promotional gem, one that helps tout the selling points of Kansas City to the world: The Command and Staff General College at Fort Leavenworth. By bringing in young, promising and relatively high-ranking members of other nation’s military forces for studies there, the CGSC is, in effect, seeding the world with rising military minds who understand not just tactics, but the roles of military force in free societies.

“They average 120 international students every year,” Denning said, “and most of them bring their spouses with them. They are getting the opportunity to travel the U.S. and get an understanding of our culture and appreciation for democracy and freedom and everything the U.S. has.”

That has already paid off, he said, in the numbers of program graduates who have gone on to become the top-ranking officials in their nation’s militaries, and even move into civilian roles as elected leaders in a few countries. Try putting a dollar value on what it means to have such leaders with positive feelings toward the U.S. “It’s not a surprise,” Denning said, “that they would only send their best, and that bears out. These guys and gals end up being the leaders of their nations’ military not too far in the future.”