HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

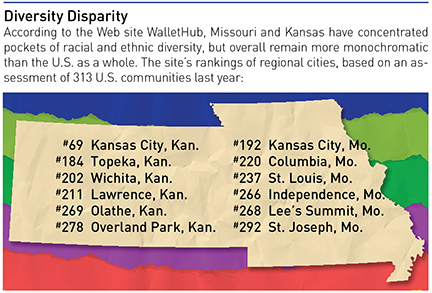

Two incidents rooted in the challenging subject of race relations—the Ferguson riots in 2014 and the student protests on the MU campus in Columbia last fall—thrust Missouri into a national spotlight, with media reports portraying the state in ways that weren’t particularly flattering.

A lot of nuance was lost in discussions about those two events, but for academics, corporate diversity managers, executives and others, some new questions have arisen about how diversity programming can be improved, and whether efforts to embrace the concept have been truly effective.

“To understand that, you have to understand the evolution of diversity through the years,” says Susan Wilson, vice chancellor for diversity at inclusion at the University of Missouri-Kansas City. At that point, she leads an enlightening tour of diversity thought going back decades.

“It started with an affirmative-action focus, looking at quotas before they were outlawed, and was really focusing on compliance with civil-rights laws,” she said. “Then it moved into a phase where everybody was developing programming, but the idea of diversity wasn’t really integrated into the mission, vision or business case for diversity.”

A great many well-intentioned companies, she said, ended up chasing solution that would deal only with the surface level of diversity—they failed to apply an organizational-development aspect. That has led to what she calls Diversity 3.0: “If you don’t identify the business case for diversity, there’s no compelling reason to continue to do it,” Wilson says.

Kori Carew, director of strategic diversity initiatives at Shook, Hardy & Bacon—among the region’s biggest law firms, and frequent winner of awards for diversity programming innovation and achievement—wasn’t surprised by the types of reactions to events that put the state in the headlines. “Speaking for myself and many that I know and work with, we do not see this as something that is new,” she said. “It’s been brought to light because we live at a time where information is shared so much more readily. But this isn’t a Missouri issue; it’s a national issue.”

So has something been missing with diversity initiatives? Perhaps, say D&I executives, and a key piece may be an organization’s commitment to fully address unconscious bias.

“The thing that seems to have the most relevance or sense of urgency, but has been around quite some time, is the issue of unconscious bias, or implicit bias,” says Michael Gonzales leader of corporate diversity and inclusion for Hallmark Cards. “It’s an awareness of who you are as a person, and being conscious of that as you’re making decisions, whether in hiring, promotion, marketing, or community impact decisions. You need to be aware of what you bring to the table in those processes, but it’s such a wide shoreline that it’s hard to tackle all of that at once.”

Hallmark, he said, has engaged in extensive efforts to address such deep-seated bias, but it’s not alone: Gonzales was part of a group of diversity and inclusion executives from other companies in the region who brought national speakers to the region late last year for a summit on the topic of unconscious bias.

“The reason it’s so key is that it answers the question about why we haven’t made more progress,” Wilson said. “It answers the question of how can seemingly well-meaning people who say they understand their diversity efforts still engage in unfair practices. Even though people are well-intentioned, our behavior doesn’t always mirror our intentions or our stated belief systems. We have biases that are unconscious, and when they are, we can’t act on them to change them.”

That’s not an excuse for companies to stop trying. With leadership from the top, diversity officers say, organizations of all types can aggressively review policies, procedures, programs and engagement at every level, and produce an action plan with rigid timetables and specific deliverables. But if it’s really going to work, they say, it also must be followed up with more of that same introspection. Corporate inertia, turnover and shifting organizational priorities can combine to cover even the most intricate diversity plans with dust, if they sit on a shelf long enough.

Further complicating things is that the very definition of diversity itself continues to evolve. Once relegated to matters of race, then gender, it has expanded to encompass sexual orientation, physical handicaps and other traits.

In Shook’s case, successful programming starts with honest discussion, Carew said. But that requisite honesty is something a lot of companies want to avoid when it comes to sensitive issues.

“One of the things I do in terms of these programs is, we don’t get into matters of who is right and who is wrong,” she said. “What we do is focus on the underlying issues and the various perspectives that may lead people to feel why they feel the way they do.”

There’s a certain vulnerability that managers and employees have to embrace for that kind of communication to be effective. At Shook, Carew said, “it’s OK to try on a different perspective. You may come to a table believing one particular thing. To be able to be honest, when someone shares their perspective it may hurt, but you may need to say it hurts, and explore the reasons why. It’s very hard to not get into the specifics, the he said/she said, and to focus on the merits of the underlying issue.”

Corporate diversity extends well beyond the realm of HR, as seen in the evolution of diversity-buying programs. The Mountain Plains Minority Supplier Development Council, which covers Kansas and Missouri, was founded in 1974, the Kansas City affiliate is nearly as old. A key figure in its founding was Drue Jennings, the former CEO of Kansas City Power & Light, where Maria Jenks carries on part of his vision as vice president for supply chain.

In her role, she oversees efforts to diversify purchases of “everything from paper clips and paper to computers and servers to the services we procure” at a company with nearly $2.6 billion in annual revenue. “We have internal goals around our diverse spend and strive to grow that percentage every year,” and the company has seen solid growth in each of the six year’s she’s overseen those functions.

The challenge to that growth, she said, is in the underlying numbers of companies certified as minority-owned, women-owned or veteran-owned, in part “because we try to provide a local lens on it, to allow local companies to earn our business as well,” she says. The hunt for qualified businesses entails working with diversity-based chambers and other business-development groups, seeking out business fairs and conferences and attending procurement one-on-one sessions. “If you want diversity to be a priority, you’ve got to work at it and manage it,” Jenks says. “We’ve been successful growing our program that way, and that’s challenging in a capital-intensive business like ours—finding those who can work on big projects isn’t always easy.”

All of this takes a lot of work, diversity executives say, but the payoff will show up with a work force that is less prone to turnover, exhibits a higher level of collaboration across and within departments, and suffers less interoffice conflict.

Gonzales said Hallmark went through a series of 26 sessions, presenting detailed information on strategic diversity initiatives for 3,000 employees, as part of its commitment to tapping into resources that might otherwise be overlooked within the company. “Our signal of success is when business managers are knocking on our doors and asking if we can present this to their division,” he said. “But will they knock? They have been for more than 2 years and it’s holding steady.”

Successful initiatives, Wilson said, will focus not just on programs, but how they tie into mission and vision. “As much as organizations can institutionalize practices, if you look at diversity in general the past 20 or 30 years, it ebbs and flows, based on who is in office, who’s in leadership. That’s why it’s so crucial to institutionalize those efforts, so that no matter who is the leader, that kind of programming and approach remains. As we move to a more global economy—we’re already in one—the business imperative is more and more salient.”