HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

HOME | ABOUT US | MEDIA KIT | CONTACT US | INQUIRE

A beautiful spring morning in North Kansas City starkly contrasted with images of 19th-century London, but a nearly Dickensian theme—the best of times, fraught with some uncertainty—presented itself May 12 at the 17th annual Construction Industry Outlook Assembly, which drew a capacity crowd to the meeting room at the Builders’ Association Training Center. More than 30 executives from leading companies in the construction sector gathered at the event, co-chaired by Don Greenwell of The Builders’ Association and Mark Heit of McCarthy Building Companies, the assembly’s sponsors. In a fast-paced two-hour discussion that couldn’t begin to cover all the topics on the agenda, they explored changes—not all of them positive—in the local, regional and national markets, evolving sectors, the impact of technology, public policy, work force issues and much more. It was a powerful reminder that as goes the health of our construction sector, so goes the economic vitality of a region comprising many interdependent organizations.

As an opening question, participants were asked to envision conditions a year from now, and apply a headline to them. Their answers bespoke a wide variety of perspectives about what works in construction, and where the sector needs to focus some attention.

As an opening question, participants were asked to envision conditions a year from now, and apply a headline to them. Their answers bespoke a wide variety of perspectives about what works in construction, and where the sector needs to focus some attention.

Among those offering sunnier shades of optimism was Tom McVey of Clark Enersen Partners, an architectural and engineering firm. “We just celebrated our 70th anniversary,” he said, “and our 70th year was our best ever.

Bill Prelogar of NSPJ Architects, too, is feeling the rush of business. “We’re busier than we’ve ever been—and I expect to be even busier next year,” he said.

To that point, Lockton Companies’ Chuck Teter wrote a headline that declared, simply, that Multifamily and Commercial Will Continue to Boom. Ryan Neighbors, of multifamily specialty firm Neighbors Construction, couldn’t have agreed more. “The hits will just keep coming,” he said, noting the company’s healthy backlog of work. “At first, we thought 2016 would see a slowdown, then 2017, and now it looks like 2018” at the earliest. But the heights that market has reached for several years now hint of a significant potential drop-off thereafter.

Some views of what may lie ahead, however, implied that things are less than rosy right now within the sector, including those of Carlos Setien of Contract Services Corp. He addressed a measure of inequality he sees in his work by saying, “I hope women-owned and minority businesses are allowed to participate in growth in the private sector,” as well as in the public-sector work were more projects are specifically directed their way.

In a similar vein, Joe Mabin of the Minority Contractors Association wrote a headline that was tinged with disappointment, but nonetheless hopeful: In addition to minority- and women-owned businesses sharing in the continuing expansion, he said, he sees a 2017 where “we have more opportunities to integrate the skilled crafts.”

Tom Buchanan, senior partner with McDowell, Rice, Smith & Buchanan, offered a take that tied in with Setien’s: All contractors will likely be looking for gains in the private sector, because “I don’t expect major expenditures in public works at the state or local level,” he said.

An undercurrent of labor distress ahead framed the outlook for Mary McNamara of Cornell Sheet Metal and Roofing. “I think we’re all going to have to continue to figure out how to do more with less,” she said.

JE Dunn’s Lynn Newkirk said the outlook at this point for 2017 was for a slight decline in revenues. But even a small step back would still be considered a very good year, he said, in light of the robust billings that will run through 2016.

For Justin Apprill of U.S. Engineering, cutbacks in proper maintenance by many property owners—through both the long downturn and prolonged unevenness of the recovery—has led to a surge in work to address deferred maintenance. Not so good, perhaps, for those who invariably would pay more for being penny-wise, but welcome news for those who do the actual upgrades and repairs.

Into all of that tea-leaf reading, Angie McElhaney, a partner with the accounting and consulting specialist MarksNelson, injected an additional air of uncertainty: “This time next year, we’re going to have a new president,” she said.

All of which prompted Susan McGreevy, a development-law specialist with Stinson Leonard Street, to issue a declaration that was in part an uplifting challenge to proven competitors and part-cautionary warning to the faint of heart: “In 12 to 24 months,” she said, “we’ll know which of you were good enough as managers to get past the labor, pricing and other issues.” Those in the room had already demonstrated their competence at the task of building things, she said—now it’s time to be prepared to manage through a period of comparative lean.

Asked to identify which construction disciplines were seeing the greatest changes, through growth or contraction, Bill Prelogar immediately singled out the senior-housing market. The oft-cited figure is that 10,000 people in the U.S. surpass the age of 65 every day within the Baby Boomer cohort, and while they’re not ready for the retirement home yet, they will be before long. And we’re going to need a lot more of those facilities.

What’s happening in senior housing already, Prelogar said, “is a pretty strong reflection of developers’ per-ceptions of changing demographics.” The first Boomers started turning 65 in 2011, meaning they’re past 70 now, and demand for independent living space starts picking up in one’s late 70s—just a few years from now. That will be followed by demand for assisted-living space as those in that cohort surpass their 80th birthdays.

Don Greenwell pointed out that a rebound in housing prices would trigger more movement into senior housing as older residents recaptured the home values lost in the real-estate downturn of 2008. For years following that, he said, “seniors couldn’t afford to sell their homes.”

McCarthy’s Greg Lee noted the company’s own efforts to secure office space had proven somewhat challenging. “There’s not much of that space out there,” he said, implying change coming within that key subsector.

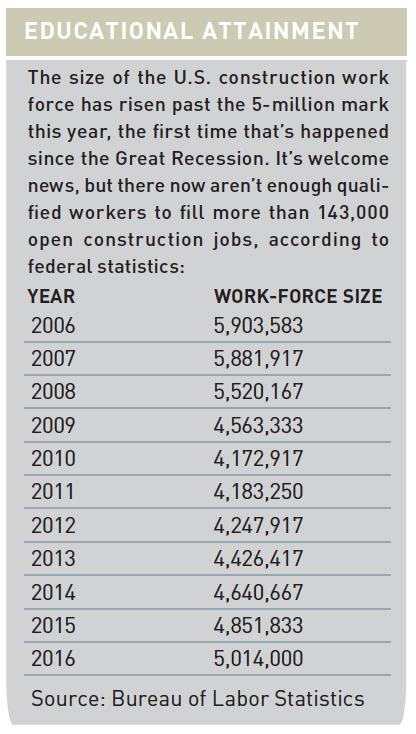

A ssessing the prolonged boom in multifamily housing, Steve Swanson of Centric Projects said that while apartments continue to go up almost everywhere you look, that niche is something that’s “not only to be in, it’s labor-intensive,” at a time when the construction work force is being squeezed. While the market itself is booming, he asked, “where are the people?”

ssessing the prolonged boom in multifamily housing, Steve Swanson of Centric Projects said that while apartments continue to go up almost everywhere you look, that niche is something that’s “not only to be in, it’s labor-intensive,” at a time when the construction work force is being squeezed. While the market itself is booming, he asked, “where are the people?”

Ryan Neighbors pointed out that many investors in residential facilities had done superbly well, because they understood that “the key is how quick you can get to market, and ready to rent.”

One final sub-market undergoing profound change is in refrigeration systems. Bill Fagan of Design Mechanical said advances in refrigerant applications, high-efficiency motors and energy-efficient chillers, fans and other systems was rapidly rendering traditional systems obsolete and cost-ineffective. On top of that the EPA’s push to phase out R-series refrigerants will have an impact that could last 10 to 15 years, he said.

The EPA example tied in neatly with discussion about public policy; construction is among the sectors that rely heavily on public spending to fill their project pipelines. The policies that shape those spending decisions, at the local, state, and federal levels will all be shifting in the wake of a presidential election looming in November, and perhaps more consequential races at the state level.

The latter suggests opportunities for policy shifts that could benefit contractors.

“It’s been unjust what’s gone on in Kansas,” said Alise Martiny, of the Greater Kansas City Building and Construction Trades Council. She was referencing the cash-strapped state’s reliance on funding from its Department of Transportation—wryly dubbed “The Bank of KDOT” by critics—to shore up the overall budget. With every seats up for election in the Kansas House and Senate, the potential for policy change next year looms large.

But the spending pinch respects no state line. “We in Missouri have to find a way to fund our highway system,” said Joe Mabin. For his part, Tom Buchanan said he didn’t think an electoral change—at any level—would produce wholesale change in spending priorities. “I’m not planning for a sea of change,” he said.

As Parker Young of Straub Con-struction pointed out, though, “a presidential election still matters.” Not necessarily because of the specific occupant of the White House, he said, but because of presidential appointments, executive orders and enforcement priorities.

The room then turned to questions of how the construction sector goes about its business, in matters involving public-private partnerships, in design/build adoption, in technology that has changed operations at the home office and in the field, and even broader concerns about how a region sets its priorities for large-scale projects that might attain iconic status.

T he collaborations between public and private sectors—P3 in the vernacular of those in the industry—still present some opportunities for construction growth, said Brett Gordon of McCownGordon Construction. Projects like the National Nuclear Security Administration campus in south Kansas City and the IRS headquarters Downtown had demonstrated the value of those partnerships, he said.

he collaborations between public and private sectors—P3 in the vernacular of those in the industry—still present some opportunities for construction growth, said Brett Gordon of McCownGordon Construction. Projects like the National Nuclear Security Administration campus in south Kansas City and the IRS headquarters Downtown had demonstrated the value of those partnerships, he said.

“There is value in large-scale delivery,” said Justin Apprill. The highly publicized proposal to build a single-terminal airport where Kansas City International stands today, he said, “would be a tremendous opportunity—think of how exciting that would be.” While that project would clearly benefit contractors and subs, Brett Gordon noted that as it now stands, the new airport wouldn’t fit traditional P3 modeling. “It’s quasi public/private,” he said, “since the industry and business would be paying for the airport.”

Even though only five such projects took root last year, “The trend will continue,” said Lockton’s Mike Campo.

Carlos Setien suggested that the region should rethink its approach to iconic structures. Nearly 50 years ago, Kansas City was able to envision and build the original KCI as well as the Truman Sports Complex—each of which have since undergone renovations worth more than a combined $1 billion. “Architecture provides an image of who we are as a city and our history,” he said, but if we’re going to replicate the successes of the 1970s, private money is going to have to flow toward those goals—much as it did to finance the Kauffman Center for the Performing Arts, the most recent icon added to the Downtown skyline.

As for technology, Greg Lee pointed to the impact of 3-D computer modeling, through programs like Revit and Building Information Modeling. “That has changed our culture,” he said. In a similar vein, Greg Carlson of Burns & McDonnell cited the significant improvements in efficiency that technology had produced.

Carlos Setien, however, said tech had its own dark side, arguing that it had created a misdirection with respect to the requirements of the actual work. At times, an information overload means “we forget to pay attention to the critical details,” he said.

Joe Mabin also had concerns about the way technology was being applied in the sector. “It is limiting the growth of minority and women contractors,” he said, because being smaller, they generally can’t compete with the technology spend of large contractors, and are thus at a bidding disadvantage because they can’t realize the improved margins brought by those very systems.

That topic provided a segue into changes in the work force reliant on that technology. The Builders’ Association’s Richard Bruce, who oversees the Training Center said employers in the sector were no longer looking simply for a pair of hands to hire. “They’re looking for knowledge workers,” Bruce said—the kinds of people with the critical-thinking skills to leverage the potential gains that technology affords.

Steve Swanson believes that the younger workers entering the field—Millennials—“don’t know how to talk with people,” and as a consequence, they are lowering overall levels of collaboration. Ryan Neighbors concurred: “The speed and volume of communication detracts from field managers,” he said.

Steve Swanson believes that the younger workers entering the field—Millennials—“don’t know how to talk with people,” and as a consequence, they are lowering overall levels of collaboration. Ryan Neighbors concurred: “The speed and volume of communication detracts from field managers,” he said.

Mary McNamara, however, said it’s not the technology at fault here: It’s process. “You have to take your work force and train them in how to

effectively communicate with each other.” That, she said, contributes to a more well-rounded employee, whose home life will be improved as well with better communications skills. She brought a knowing chuckle from many in the room when recounting the story of a new hire who asked her for someone to do his typing for him.

Bill Prelogar said that over the past decade, “I’ve seen my (office) phone go dead, while my e-mails have skyrocketed to 150 or 175 a day.” Much of that traffic, grounded in requests for information, tell him that “there’s been a huge shift toward CYA project management.”

“More information is not better,” Steve Swanson declared. “Better information is better,” and he said it was unrealistic to expect field supervisors to process huge volumes of information on-site, where the work has to get done.

Following a short break, the discussion resume with Mark Heit posing this vision of the near future in construction: “Those that control labor will control the marketplace.” One example fraught with the potential for wrenching change is robotics, where McCarthy has taken its first step to assess robotic masons.

Ryan Schultz, of RS Electric, laid some of the current work-force challenge, again, at the feet of Millennials who, he said, “don’t want to do the work.” Carlos Setien was prepared to argue—at some length—that a huge cohort of willing workers could be accessed with a more liberalized view toward immigration, but as Heit diplomatically pointed out, “we’re not going to resolve concerns involving immigration here today.”

Angie McElhaney said the lack of skilled workers was impeding the ability of some companies to grow. “They’d love to bid on a project,” she said, “but can’t because they don’t have the people. It’s hampering the entrepreneurial spirit.”

The ultimate impact of that shortage, said Chris Vaeth of McCownGordon Construction, falls on owners. “Money on the sidelines won’t get spent if they can’t make the investment work,” he said.

Supply and demand is kicking in with wages, and Ryan Neighbors said that a lot of subcontractors “are dying on the vine.”

It’s all part of a larger societal issue, said Parker Young, stemming from a push to get young people into college, even if it’s not the right fit for them. “We’ve got to get out as an industry and work together on this,” he said. With a career as a skilled craftsman “you can make a good living, you can save for retirement, you can still have the American Dream.”

It’s all part of a larger societal issue, said Parker Young, stemming from a push to get young people into college, even if it’s not the right fit for them. “We’ve got to get out as an industry and work together on this,” he said. With a career as a skilled craftsman “you can make a good living, you can save for retirement, you can still have the American Dream.”

Then, too, changes in school curricula have played a role. “There was a time,” said Joe Mabin, when you could hire bricklayers right out of high school” because they had been exposed to industrial-arts classes that are increasingly hard to find.

Alise Martiny followed with an impassioned appeal for contractors to stop focusing on margins and do more to bring on inexperienced workers, cracking the chicken-and-egg dilemma of not hiring those with expertise, but leaving the younger generation locked out for lack of it.

“You all look for the journeyperson,” she said, “and there’s no money for training. There are so many who want to go to work but won’t until there’s a change in margins. We need to include apprentice people in job budgets.”

“We have lost,” Bill Fagan said, “a whole generation of apprentices.”

Justin Apprill suggested that other contractors turn to organizations like the National Institute for Construction Excellence, based right here in Kansas City, for guidance on how to connect with high-school students who might be prospective employees. “I grew up in the industry,” he said, but the overwhelming majority of students aren’t similarly exposed to the benefits of a career in construction trades.

Mary McNamara cited a program in the Independence school district, where all three high schools supply the students needed for a construction-studies program that has them actually building a home.

Mitch Hoefer of Hoefer Wyscoki Architects pointed out a recent development that was addressing the talent issue—the transformation of Downtown Kansas City, and the region’s growing appeal as a place for young adults to live. “We’re recruiting from across the U.S.,” he said, and prospects who used to limit their searches to cities like Chicago now find that Kansas City is an attractive alternative. “It looks great to them, plus we’re keeping more of our own here,” he said.

Mitch Hoefer of Hoefer Wyscoki Architects pointed out a recent development that was addressing the talent issue—the transformation of Downtown Kansas City, and the region’s growing appeal as a place for young adults to live. “We’re recruiting from across the U.S.,” he said, and prospects who used to limit their searches to cities like Chicago now find that Kansas City is an attractive alternative. “It looks great to them, plus we’re keeping more of our own here,” he said.

Eddie Whitley, whose drywall specialty company, Whitley Construction, might have been one of the smaller businesses at the table, pointed out that engagement from leadership can make a difference. His Lee’s Summit business engaged an intern from the inner city,

but when that employee ran into transportation challenges and risked dropping out, Whitley and his staff found ways to share the task of bringing him to work.

The depth of the challenges in matching the different value sets of an emerging work force with traditional work flow and project development was evident with the group’s largely shared concerns about work ethic, Millennial desires to have not just work-life balance, but a work-life blend that integrates the two, and a desire not to be stuck alone behind a desk all pointed to challenges looming for construction management, challenges that likely will travel far with those companies on the road ahead.